Potter & Potter Takes a Gamble

May 7th, 2017

Potter & Potter Auctions, Chicago, Illinois

Photos courtesy Potter & Potter Auctions

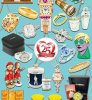

Snug in a corner of an American gambler’s chest from around 1880, surrounded by chips, dice, a cigar cutter and holder, playing cards, and a scrimshawed ivory-handled pocket knife, lay an engraved pistol with a mother-of-pearl handle.

“It might be needed if a guy was cheating and had to defend himself,” said Gabe Fajuri, president of Potter & Potter Auctions in Chicago, which sold almost 1100 pieces of gambling memorabilia on May 6 and 7. It was the biggest sale to date for the firm known for its magic and circus memorabilia auctions.

The chest, which sold for $6600 (includes buyer’s premium), against a presale estimate of $3000/5000, was said to be one of the few to come to auction with apparently all-original materials. That the box contained numerous ivory items—a dagger handle, a chips compartment lid, the knife handle, and a dice cup—added to its authenticity but presented a problem for the sale.

This American gambler’s box from around 1880 was one of a number of auction pieces containing ivory, prompting one online auction platform to refuse to list it. Hidden beneath the dice, mother-of-pearl chips, a cigar cutter, and other items was a revolver. Ivory was obvious in the lid of a chips compartment, a dice cup, and the scrimshawed handle of a pocket knife. With all parts thought to be original, the box went for $6600.

The LiveAuctioneers online auction platform removed all ivory items from Potter & Potter’s online catalog before the sale, maintaining that it didn’t want any hassle from federal authorities for promoting the sale of ivory, Fajuri said. Bidsquare and Invaluable kept the catalog intact.

The disparity put the auction house and consignors of ivory items such as chips, markers, tops, and ornamental boxes at a disadvantage, Fajuri said.

“We debated [selling the ivory] for a long time—how exactly to do it,” he said, ultimately concluding that what Potter & Potter accepted into the sale represented the era of the 19th-/early 20th-century world of gambling and was appropriate alongside the other paraphernalia.

After the auction, Fajuri said, “The ivory sales were affected, for sure. Some items did well, but overall I thought that the sales were anemic.”

The sale of ivory has been restricted by the federal government in an effort to combat the trafficking of wildlife. The latest revisions, issued in 2016, exempt ivory that is 100 years old or older, but the seller must prove age through a detailed history of the item or an appraisal. Newer ivory can be sold if it meets a number of conditions, including that it not compose more than 50% of an item by volume.

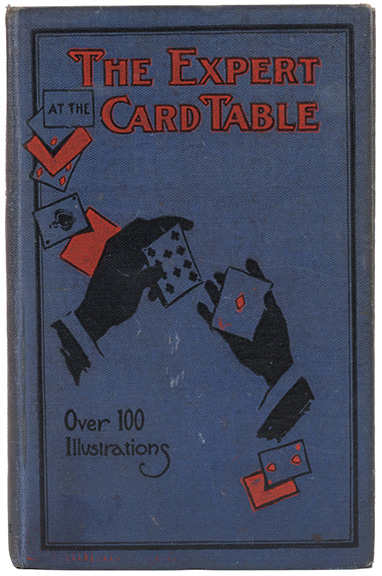

Some highlights of the sale were tools and guides for the gambler trying to get a leg up on his playing companions. A first edition copy of the 1902 book The Expert at the Card Table by S.W. Erdnase, the pen name of a Chicago author whose identity has remained a mystery despite decades of sleuthing by an enthusiastic, dedicated fan base, drew considerable interest.

This 1905 edition of S.W. Erdnase’s The Expert at the Card Table, published three years after the original, is bound in blue cloth stamped in black and red. It went for $5760, a little over half of what the first edition (not shown) fetched—$10,200. The author’s identity remains a mystery, adding fuel to the passions of the author’s dedicated fan base.

“There’s such a mania about collecting Erdnase,” Fajuri said. “First, the book is great. Then there’s this mythology that has sprung up around him—that he was a gambler who got murdered, or a lot of different theories.”

Over the years, Potter & Potter has had several Erdnase books, selling them for between $2000 and $13,200, Fajuri said. This edition went for $10,200 (est. $7000/9000). A blue cloth-covered version of the book, published three years later in Chicago, also went above its estimate, bringing in $5760 (est. $2000/3000).

An excerpt of the preface by Erdnase illustrates the writer’s wry humor: “In offering this book to the public the writer uses no sophistry as an excuse of its existence.… It may caution the unwary who are innocent of guile, and it may inspire the crafty by enlightenment on artifice.… But it will not make the innocent vicious, or transform the pastime player into a professional; or make the fool wise, or curtail the annual crop of suckers; but whatever the result may be, if it sells it will accomplish the primary motive of the author, as he needs the money.”

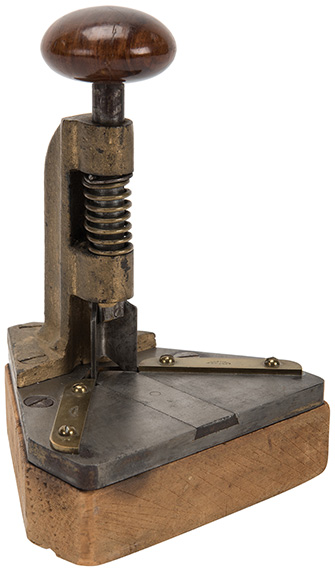

Cheaters might use this Will & Finck corner rounder to help conceal cards on which the edges were trimmed to make them easier to find in a deck. Manufactured in San Francisco around 1890 and on its original wooden base, the piece was hallmarked in two places. It brought $3120.

To help cheaters, metal card trimmers shaved the edges of cards, making them easier to find in the deck. A circa 1890 version sold for $1320, close to the top of the presale estimate of $1000/1400, while a much newer device from 1980 went unsold. Once card edges were trimmed, the corners had to be rounded to be less obvious. A brass and steel rounder, circa 1890, sitting on the original wood base, fetched $3120, handily topping the estimate of $1200/1600. If those tricks weren’t sufficient, a tension device called a “holdout” could be strapped to an arm under a shirt. Pushing on a spring would release a particular card. A circa 1920 version of aluminum and brass sold for $1560 (est. $1000/2000), while a 1980 version of brass and steel went for $1080 (est. $1200/1800).

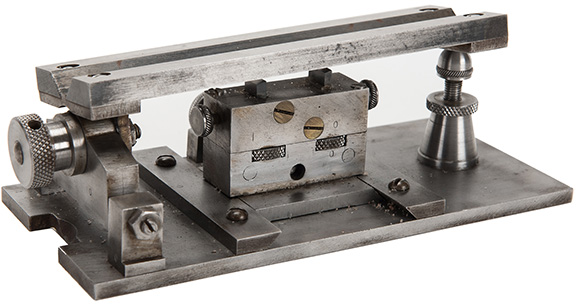

Dice also could be altered. A heavy cast steel device with the triangular hallmark of Graham, the manufacturer, shaved dice so they could be better controlled. With a reserve of $800, it went for $960. Dice cups, such as a leather “butterfly” version from 1990, had two compartments that the operator switched between as needed by pressing and twisting the bottom. It went for $2640, doubling the $1200/1800 estimate. Dice also could be stamped as though they came from a casino. More than 80 stamps depicting anchors, dogs, hearts, and other emblems, considered the property of professional counterfeiters because casino suppliers typically destroyed the plates of their dice, went for $1080 (est. $500/750).

Dice could be shaved with precision using this heavy cast steel device in an effort to make the results of rolling them more predictable. The triangular hallmark of the manufacturer, Graham, was on the piece produced around 1950. The auction catalog said verbal provenance traced the device to the “notorious dice maker ‘Junior’ Hunter Hinson.” With a reserve of $800 and estimated at $800/1200, it sold for $960.

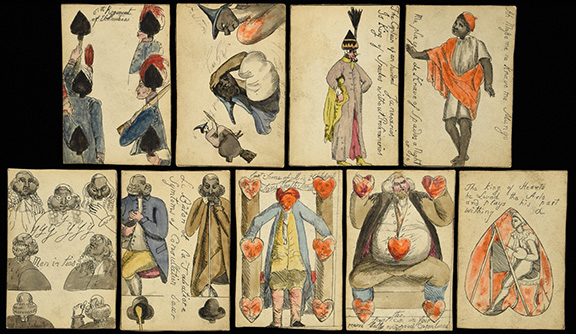

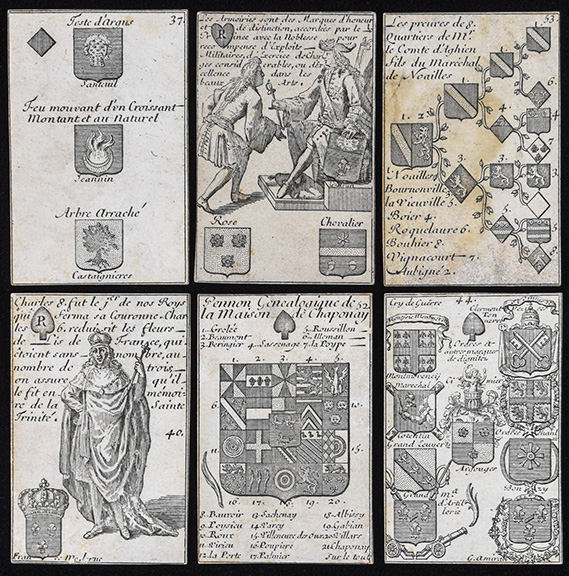

Precision marked the equipment that allowed “gaffing” (cheating) and, in a very different way, the playing cards, many of which had been consigned to the sale by Rhonda and Bob Hawes. The Connecticut collectors were selling as part of downsizing and moving. A circa 1870 German miniature set, with cards no bigger than a fingernail, said to be perfect for a dollhouse, sold for $60 (est. $100/200). Transformation cards, or those incorporating the four suit symbols into often elaborate scenes, were the Haweses’ special interest. A circa 1900 hand-painted watercolor set with male and female figures fetched $240, only about half of the $400/500 estimate. An artist with a more delicate touch drew a set around 1900 that included handwritten notations in English on each card. It was estimated at $800/1000 and went for $780. A set of 52 cards, each bearing signs of heraldry and inscriptions about bearing arms, was made in France around 1720. Estimated at $4000/6000, it went for $2400. Another 52-card set from France, circa 1868, with three of the four pips decorated with flowers and birds, and the spade pip being a spear point, was estimated at $6000/8000 but didn’t sell. More than 20 decks of cards sold after the auction ended, Fajuri said.

This set of playing cards, thought to be English and from the late 19th century, is called transformational, meaning that the pips are incorporated into period scenes. Each of the cards has a handwritten note. The set sold for $780.

This circa 1900 set of cards, hand painted in watercolor, incorporates the suit symbols so cleverly that some are hard to decipher. There are no court cards in the deck. It sold for $240.

Dedicated to the duke of Burgundy, this set of playing cards displays symbolic figures, and each has an inscription lauding the right to bear arms. The French set, dating to 1720, is considered a teaching or historic deck, but it can be used for playing because each card is numbered and has a letter inside the pips—R for king, D for queen, and V for Jack. The presale estimate was high, $4000/6000, and the cards sold for $2400.

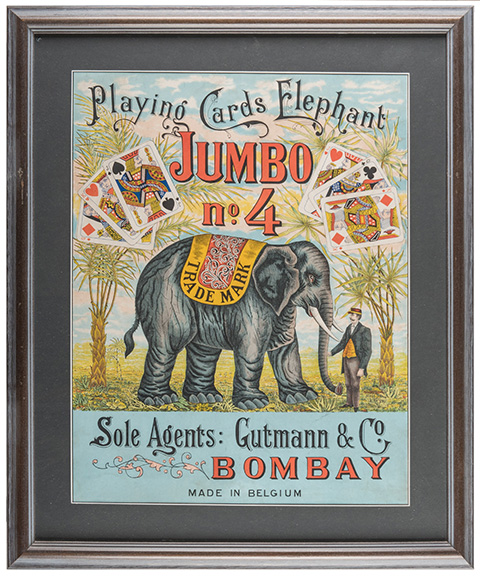

This Belgian lithograph by Van Genechten, circa 1900, uses the famous circus elephant Jumbo to advertise playing cards. The 25½" x 21" framed piece sold for $780.

Mills Novelty Co., Chicago, manufactured this bar-top 5¢ cigar trade stimulator called “The Trader” around 1905. Depending on the poker hand displayed in five cards, the player would win a requisite number of cigars. All original, with the likely exception of the award card, the machine was heavily embossed with Victorian figures and foliage. It sold for $15,600.

For a little more action, gamblers could try their luck on any number of machines—roulette wheels, slots, or trade simulators—and not always for money. Circa 1905, the Mills Novelty Co., Chicago, produced “The Trader.” For a nickel, the cast-iron tabletop machine, heavily embossed with Victorian women and foliage, would display a poker hand. The payout was in cigars from the bartender. With a hefty presale estimate of $20,000/25,000, it went for $15,600. A tall-case slot machine, also made in Chicago, paid homage to Admiral George Dewey with his portrait at the center of a patriotic shield against a very colorful tin wheel. The nickel machine on cast-iron legs, made around 1900 by Watling Mfg. Co., was mostly original, but the glass and possibly the back door had been replaced. Estimated at $20,000/25,000, it did not sell.

Gambling often spilled over into the arts. Well-known American artist Larry Rivers (1923-2002) turned the queen of hearts into a 30" x 22" color lithograph. The signed and dated (1979) artwork was number 12 of an edition of 200, and it sold for $960 (est. $1500/2000). A Belgian lithograph of the famous circus elephant Jumbo advertised playing cards. It fetched $780 (est. $1000/1500).

Bidders appreciated quirky items used by gamblers and in gambling. A set of red-tinted contact lenses, in a faux-leather-covered case and with a short metal tube capped on either end, drew an unexpected $1560 (est. $300/350). They sold with a modern set of red-tinted clip-on sunglasses used to read cards. A heavy metal shiner ring, circa 1920, fitted with a tiny mirror in place of a stone, far exceeded the $250/350 estimate to sell for $2640. It allowed for the discreet reading of cards as they were dealt. And finally, three double-sided coins, not expected to bring much more than their face value of two quarters and a half-dollar, yielded $540. The successful bidder apparently liked the odds of always winning a coin toss.

Bidders appreciated quirky items used by gamblers and in gambling. A set of red-tinted contact lenses, in a faux-leather-covered case and with a short metal tube capped on either end, drew an unexpected $1560 (est. $300/350). They sold with a modern set of red-tinted clip-on sunglasses used to read cards. A heavy metal shiner ring, circa 1920, fitted with a tiny mirror in place of a stone, far exceeded the $250/350 estimate to sell for $2640. It allowed for the discreet reading of cards as they were dealt. And finally, three double-sided coins, not expected to bring much more than their face value of two quarters and a half-dollar, yielded $540. The successful bidder apparently liked the odds of always winning a coin toss.

For more information, check the website (www.potterauctions.com) or call (773) 472-1442.

Originally published in the July 2017 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2017 Maine Antique Digest