A Bard, Ben, and a Blizzard

January 24th, 2016

Sotheby’s, New York City

Photos courtesy Sotheby’s

Sotheby’s had so much to sell this January—more than 1000 lots from the Schorsch estate (see pp. 29-33-C), 96 lots of folk art from the Levins (see pp. 36-37-B), and 406 lots from various owners—that it was hard to find enough time to see it all and bid. Sotheby’s session for China trade, rugs, and silver went head to head with Christie’s Zaitz sale (see pp. 26-28-C) and silver on Friday. On Saturday, January 23, the Levin sale went on as a blizzard closed down New York City. The 2 p.m. session of various owners’ prints, furniture, and folk art was rescheduled from January 23 to Sunday afternoon, January 24, at 2 p.m. Many who had come to stay for the week left on Friday before the blizzard arrived and were resigned to bidding by phone or online.

Though a real buzz, which used to be part of every January auction, was not created, the three dozen stalwarts who arrived for this sale on Sunday bid with gusto. The phones were busy. A few strong prices were paid. But of the 406 lots offered, just 300 sold for $3,569,439 (with buyers’ premiums). That is about 74%, a reflection of this selective market. It is hard to sell things of modest value in New York City. Some great rarities of high aesthetic merit were not overlooked.

A collector came to the sale to buy a majestic life-size elk by Joseph Winn Fiske of New York, 1892-1900. Standing over 9' tall, it retains its original patina. The seated collector outbid a phone bidder and paid $225,000 (est. $50,000/100,000). The Fiske elk, perhaps based on a design by the Berlin sculptor Christian Daniel Rauch (1777-1857), is considered one of the greatest pieces of outdoor garden statuary.

When new, this life-size sculpture of an American elk cost $210, a high price, so few were created and few survive. The bronze-painted cast zinc and cast-iron elk, 1892-1900, is by J.W. Fiske, New York. The surface is weathered and the base is marked “J.W. Fiske N.Y.” The 112" high, 30" wide, and 75" long sculpture sold for $225,000 (est. $50,000/100,000).

Westborough, Massachusetts, dealer David Wheatcroft, bidding by phone, was the buyer of a painting of the schooner Norma by James Bard, paying $200,000 (est. $150,000/250,000) on behalf of a client. According to the catalog, of the 459 known Bard paintings, only 19 are of sailing vessels, each one built in the area of Nyack, New York, including the Norma, built in 1852. Her home port was Cold Spring, in the Hudson highlands, where she was engaged by the West Point Foundry to haul water pipe and iron fencing from downstream clients and later cannonballs for the Union army. The buyer bought a good story and a stunning painting.

The Schooner “Norma” was painted by James Bard (1815-1897), dated 1858, and inscribed on the lower left “Owners / Marcus Sayre / Wm. B. Cutter / Hirum Aderson / Dimensions / Length of Keel 64 ft. / Breadth of Beam 25 Ft. / Depth of Hold 5 Ft.” The 32½" x 51½" oil on canvas sold for $200,000 (est. $150,000/250,000) to dealer David Wheatcroft of Westborough, Massachusetts, for a client. At Sotheby’s in January 2001, it had sold on the phone for $247,750. Of the 459 paintings by Bard, only 19 are sailing vessels, all built in the Nyack, New York area. Tony Peluso, quoted in the catalog, called this painting “a fine Bard, in generous size and remarkable condition. She races across the Tappan Zee….”

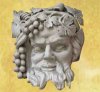

The most exciting discovery of the week was a carved and painted pine bust of Benjamin Franklin, cataloged as “one of the best eighteenth-century sculptures of Benjamin Franklin known.” It was not unknown. Tom Armstrong, Wayne Craven, and Norman Feder included it in the exhibition 200 Years of American Sculpture at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1976 and had described it as by William Rush. In the 1982 exhibition William Rush: American Sculptor at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), it was described as not by Rush. Linda Bantel, the curator, said it related to a figurehead Rush carved for the ship Franklin, and although the Delaware Historical Society, which owned it then, called it a Rush, PAFA curator Bantel wrote in the catalog, “the bust is unrelated to Rush’s work.” According to Sotheby’s catalog, in a report for collector Michael Zinman in 1995 researcher Keith Arbour wrote that busts of Franklin were used as architectural elements over shop doors, and it is possible that this Franklin was used on the southeast door of the House Chamber at Independence Hall. A bust was mentioned by Henry Wansey in 1794 as being on the main entrance to the House Chamber in 1793. That entrance was demolished in 1812. But who carved the bust? There was much speculation all week.

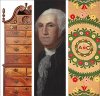

This bust of Benjamin Franklin (American, 1785-95, probably Philadelphia) sold for $175,000 (est. $20,000/30,000). Once thought to be the work of William Rush, it was included in the 1976 exhibition 200 Years of American Sculpture at the Whitney Museum of American Art, curated by Tom Armstrong, Wayne Craven, and Norman Feder. The Rush attribution was refuted by Linda Bantel when she curated the exhibition and catalog for William Rush: American Sculptor at the Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. In the 1930s the bust was bought by dealer David Stockwell, and it was at the Delaware Historical Society before it went to the private collection of the consignor. Paint analysis revealed many layers of paint and varnish. Scholar Keith Arbour suggested it may be the bust described by Henry Wansey in his Excursion to the United States of North America in the Summer of 1794, published in 1798, where he described a bust of Franklin on the southeast portico of the State House (Independence Hall), which is now demolished. If not by William Rush (1756-1833), then who carved it? Answer: Martin Jugiez, according to the buyer, Alan Miller, who was acting for the Chipstone Foundation in Milwaukee.

After he was the successful bidder on behalf of the Chipstone Foundation in Milwaukee, furniture scholar Alan Miller revealed that he sees in this Benjamin Franklin bust the hand of carver Martin Jugiez, a Philadelphia carver of furniture. Miller pointed out similarities in the carving style and tool marks to those on a lion on a sculptural sideboard table at the Philadelphia Museum of Art that was carved by Jugiez. Look at the eyes of the lion photographed for the cover of the 2004 American Furniture journal and compare them with the eyes of the Benjamin Franklin bust. They are the same! In his 2004 article on Martin Jugiez and the lion table in American Furniture, Miller takes issue with the fact that sculptors are considered artists and carvers are called artisans. Miller called the sideboard table as much a work of sculpture as a piece of furniture.

The bust is derived from Jean-Jacques Caffiéri’s 1777 portrait bust of Franklin, taken from life in Paris and from which many copies by other artists were made. The bust is possibly earlier than any by Rush and is a masterpiece of Philadelphia carving well worth the $175,000 (est. $20,000/30,000) Chipstone paid for it. Is Benjamin Rush really America’s first sculptor?

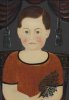

The rest of the sale reflected the unpredictable Americana market. A folk portrait by Sturtevant Hamblen of a young boy with flowers sold to a collector on the phone for $150,000 (est. $60,000/80,000), underbid on the phone by dealer David Wheatcroft for a client. In 2004 it had sold for $102,000 at the Egan sale at Sotheby’s. The current price shows that good folk portraits of children can hold value.

The rest of the sale reflected the unpredictable Americana market. A folk portrait by Sturtevant Hamblen of a young boy with flowers sold to a collector on the phone for $150,000 (est. $60,000/80,000), underbid on the phone by dealer David Wheatcroft for a client. In 2004 it had sold for $102,000 at the Egan sale at Sotheby’s. The current price shows that good folk portraits of children can hold value.

A John James Audubon American White Pelican (Plate CCCXI) sold for $118,750 (est. $45,000/55,000). A similar print sold for $116,500 at Sotheby’s in January 2012 (est. $80,000/120,000).

John James Audubon (1785-1851), American White Pelican. The hand-colored aquatint, engraving, and etching was done by R. Havell in 1836 on wove paper. The framed 38½" x 28" sheet sold on the phone for $118,750 (est. $45,000/55,000) and was the top lot of 13 Audubon elephant folio prints in the sale.

A pair of Federal inlaid and figured mahogany and birchwood games tables, attributed to John and Thomas Seymour of Boston, 1798-1805, that retain their original surface and vibrant satinwood veneers demonstrated that the finest Federal furniture is still in demand. They sold for $87,500 (est. $25,000/35,000) to a collector who left a bid with the auctioneer. They are related to a remarkable table in the Kaufman collection now at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C.

A fine pair of Federal chamber tables from the collection of Ted and Ingie Kilroy sold on the phone for $27,500 (est. $6000/8000). A mahogany bench and a matching pair of scroll-back chairs with double-cross banisters, related to the surviving chairs that William Bayard commissioned from Duncan Phyfe, sold for $13,750 (est. $10,000/15,000). The same price of $13,750 (est. $8000/12,000) bought a trick-leg mahogany and satinwood games table, attributed to Phyfe circa 1815. Back on June 19, 1998, it had sold for $28,750 (est. $8000/12,000). It is a good time to buy.

A pair of Massachusetts Federal inlaid and figured mahogany chamber tables, circa 1800, with original brass hardware, each 35½" x 36" x 16", sold for $27,500 (est. $6000/8000) Last time they sold at auction was April 15, 1972, at Sotheby Parke Bernet from the collection of Flora Ettlinger Whiting of New York City, who, incidentally, endowed the Whiting Foundation, which aids writers.

Some appealing furniture was left behind. For example, there was no interest in an assembled set of eight Federal dining chairs (six side chairs and two armchairs) that have an old surface and carving attributed to Samuel McIntire of Salem, Massachusetts, related to chairs from the Peirce-Nichols House in Salem. The estimate was $75,000/125,000. They had sold at Sotheby’s on January 18, 2003, for $176,000.

The assembled set of ten Chippendale mahogany side chairs, Boston or Salem, Massachusetts, circa 1770, sold for $43,750 (est. $12,000/18,000). The group has a set of six, a pair, and two singles, many with old surfaces.

There was no interest in some good Colonial Massachusetts furniture either. A figured mahogany serpentine-front slant-front desk with bold ogee bracket feet, attributed to John Cogswell of Boston, circa 1770, failed to sell (est. $30,000/50,000). Rarely do slant-lid desks have a single serpentine front; more common is the reverse serpentine or oxbow. Also unsold was a mahogany chest of drawers attributed to Benjamin Frothingham of Charlestown, Massachusetts, circa 1770, with a rich old surface and an Israel Sack provenance, estimated at $60,000/120,000.

The Frieze family shell-carved and figured mahogany tall-case clock with works by Edward Spalding of Providence, Rhode Island, circa 1775, estimated at $100,000/150,000, failed to find a buyer. And there was no bidding for Mary Blair Sams’s carved cottonwood tall-case clock, probably made in New Orleans, Louisiana, circa 1928, 93" tall (est. $150,000/250,000). It is inscribed on the top of the cornice in chalk, “Mother’s Old Voodoo Clock.” Cottonwood is a southern wood, and the motifs may be African American Caribbean, related to voodoo rituals.

James Bard’s The “Kaaterskill” inwatercolor and gouache on paper, 27" x 49", signed and dated 1884, estimated at $150,000/250,000, did not sell. The excuses were that there are no people on the paddle-wheeler, and it was a watercolor, not oil, and condition was not pristine.

Silver had to be exceptional to provoke serious competition. Two bidders wanted 424 pieces of Tiffany flatware service in the Shell and Thread pattern, mid-20th century; it sold for $93,750 (est. $22,000/28,000). It was consigned by the family of Morris and Adele Bergreen, who were lawyers and great philanthropists.

A Halsted & Myers coffeepot, made in New York 1763-65, was bought by a collector for $68,750 (est. $30,000/50,000). It was exhibited in New Haven in 2001 and at Winterthur in 2002 and discussed in David Barquist’s book Myer Myers: Jewish Silversmith in Colonial New York (2001). It is one of the few large pieces of hollowware marked with the partnership’s mark, H & M in a rectangle. Only about 20 objects are known with the partnership mark, a small number for an eight-year association, during which both craftsmen marked silver with their individual marks. The coffeepot is pictured in the Barquist catalog, in which he suggests that Halsted provided capital and managed the retail side of the business during the time Myers moved his shop out of the Myerses’ house.

Dealer Jonathan Trace of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, bought 36 lots of silver from the early 18th century to 19th century including a Myer Myers salver for $17,500 (est. $20,000/30,000). “I bought terrific objects that were affordable, and what I don’t sell before, I’ll take to the Philadelphia show,” he said.

An elegant silver cream pot by Thomas You of Charleston, South Carolina, 1770-80, with a punch beaded border, has engraved on the front “B/A*P” and is marked “T[pellet]Y” in a rounded rectangle on the base. It weighs 5 ounces, stands 5 3/8" high, and sold for $11,875 (est. $2000/3000). Ruth Nutt collection.

This silver coffeepot with the mark of Halsted & Myers, 1763-65, is 30 oz. 10 dwt., 10 7/8" tall, and marked in the center of the base “H & M” in a rectangle. It sold for $68,750 (est. $30,000/50,000). It is one of the few pieces of hollowware marked by Halsted and Myers; only about 20 items survive with the partnership’s mark. Ruth Nutt collection.

Though there were some successes, there were disappointments in silver sales, some of it from the vast Ruth Nutt collection. The American silver salver by Richard Humphreys of Philadelphia for the Emlen family, circa 1775, that had sold at Sotheby’s in January 1997 for $250,000 failed to sell for the second time. It was offered in January 2015, and even with a lower estimate ($150,000/250,000) failed again. It is the largest known marked Philadelphia salver of the rococo period.

Alfred Taubman’s 1785-95 Chinese export porcelain part dinner service of 113 pieces with the arms of Van Idsinga of Friesland, which once belonged to Nelson Rockefeller, estimated at $40,000/60,000, failed to sell as did another Chinese part service of 109 pieces painted in sepia with gilt flowers and a burnt orange border. A more decorative orange Sacred Bird and Butterfly pattern part dinner service of 108 pieces sold for $15,000 (est. $12,000/15,000). It once belonged to Robert Gould Shaw (1776-1853), nephew of Major Samuel Shaw of Boston, and had descended in the Shaw family.

For more information, call (212) 606-7000 or check the website (www.sothebys.com).

The Grant-Beardsley-Canning family figured maple dressing table, Windsor, Connecticut, circa 1735, appears to retain its original cast and engraved brass hardware and retains a dark, richly crazed (possibly original) surface. Measuring 29" x 36" x 22¾", case width 33¼", it sold for $12,500 (est. $5000/7000) to a collector in the salesroom.

Purportedly made for Samuel Grant (1691-1751), it had been purchased from the Connecticut pavilion at the 1904 World’s Fair from Mrs. Roswell Grant of East Windsor Hill, Connecticut. With its brilliantly figured maple, the earliest form of Connecticut cabriole legs, and its apparently original surface, this dressing table is one of only four surviving examples of the earliest form of Queen Anne dressing tables in Connecticut and relates directly to the two most famous high chests with provincial japanning. All in the group have very identifiable oversize disk-like pad feet and side drop pendants.

A figured mahogany reverse-serpentine chest of drawers, probably Salem or Newburyport, Massachusetts, circa 1785, with a dark, rich old surface, original cast brass hardware, 33½" x 39" x 22½", case width 36", sold on the phone for $27,500 (est. $8000/12,000). At the Helen and Louis Appell sale at Sotheby’s in January 2003, it had sold for $66,000 (est. $25,000/35,000), with Todd Prickett and Leigh Keno bidding against the phone bidder who won the lot.

Attributed to John and Thomas Seymour of Boston, 1798-1805, the Weld family pair of Federal inlaid mahogany and satinwood games tables with old surface, each 29½" high x 37" x 18", descended in the family of the consignor. Similar to a table in the Kaufman collection on loan to the National Gallery of Art, the pair sold for $87,500 (est. $25,000/35,000) to an absentee bidder.

Sturtevant J. Hamblen (1807-1886) painted this young boy in gray with flowers inoil on canvas. The circa 1850 painting is 27" x 21 5/8" and sold to a phone bidder for $150,000 (est. $60,000/80,000), underbid by David Wheatcroft. At the Egan sale at Sotheby’s in January 2004, it had sold for $102,000, underbid by dealer David Wheatcroft.

A portrait of a young girl in a pink gown with a ruffled collar, oil on canvas, 27½" x 19½", painted circa 1830, sold for $13,750 (est. $6000/8000).

Originally published in the April 2016 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2016 Maine Antique Digest