A Short, Stout, and Very Expensive Little Sugar Pot

November 22nd, 2014

|

Rare slip-decorated redware sugar pot, 18th century and very likely from one of the potteries in Charlestown, Massachusetts, $14,375.

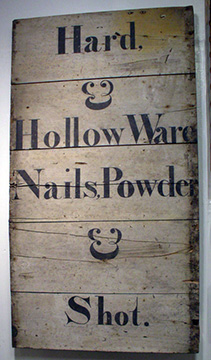

Saved from potential oblivion in a landfill somewhere, this 60¼" x 32¾" 18th-century trade sign on a wooden shingle turned into one of the sale’s leaders at $16,100.

There wasn’t much information available on this primitive watercolor of a young girl with a locket around her neck, standing with a basket of flowers in her hand, 7 1/8" x 5 1/8" (overall), only that it came to auction from a farm home in Wisconsin, but that was enough to make a major winner of it at $9775.

This 11" tall 18th-century staved wooden tankard was believed to have been given by Nina Fletcher Little to her friend Alice Andrews of Winchester, Massachusetts, back in the 1950s. It had all the original parts, a robust patina, and a robust selling price of $4025.  A terrific blockfront Chippendale chest went at $17,250. Its only detraction was its long-neglected, albeit untouched, finish.

“Small and ragged” didn’t matter much on this 15" x 25½" hooked rug. The colors were slightly faded, and the edges a bit ragged, but the folk art starry night motif with feeding lambs, a Federal house, and hearts in each corner had bidders chasing it all the way to $3737.50. “When I found that in an attic in Skowhegan, I was blown away by it,” Gould said later. |

Gould Auction Company, Gardiner, Maine

Whether it be a one-of-a-kind trade sign, a near-perfect Revolutionary War sugar pot, or a superbly grungy old Chippendale chest, “wondrous strange” objects turn up regularly with the Gould Auction Company, and its November 22, 2014, auction in Gardiner, Maine, was full of “wondrous strangeness.”

Everybody loves saved-from-the-dump stories, and an 18th-century trade sign reading “Hard, / & / Hollow Ware / Nails, Powder / & / Shot.” came with a good one. It had been painted on a wooden shutter, and it literally was rescued from a demolition heap in Worcester, Massachusetts, by a sharp-eyed picker. When he first spotted it, it was missing an arrowhead-shaped piece that had been broken out, but a little more searching through the rubble turned up the fragment, and it fit perfectly. His find turned into a $16,100 (including buyer’s premium) score. The weathering on the back conformed exactly to what one would expect to find on a shutter that had covered an 18th-century window.

Gould’s auctions are replete with fine and unusual folk art and Americana. Someone had brought in a rare, perhaps unique, form of 18th-century slip-decorated redware: a two-handled sugar pot. Gould suggested that it could be the only known surviving example from the Revolutionary War-era potteries of Charlestown, Massachusetts, that were burned in 1775 during the Battle of Bunker Hill. Except for a few minor glaze flakes, it survived all these years without any significant damage, and it found a new home at a commanding $14,375.

Several dozen such potteries existed, clustered around the Charlestown waterfront and producing works known as “Charlestown Ware.” Some ongoing archaeological work by the Massachusetts Historical Commission is still recovering artifacts from one of the pre-Revolutionary War Charlestown operations, now known as the Parker-Harris Pottery site, named after the pottery’s founder, Isaac Parker, and his inheritor, Josiah Harris. That pottery was destroyed during the Battle of Bunker Hill and never rebuilt. “I don’t think anybody’s going to argue that [the sugar pot] isn’t Charlestown,” Gould added later, “but the lid was a little different from the base.” That difference could be explained easily by the different clay compositions and firing temperatures that can occur during separate production runs.

Justin Thomas commented on the pot in his November 24, 2014, blog at (www.earlyamericanceramics.com). He believes that it was created at the Parker Pottery between 1735 and 1755, and he related it to fragments that had been archaeologically recovered from a privy at the Three Cranes Tavern during Boston’s “Big Dig” of the 1980s and ‘90s. He further noted that there was a single fingerprint on the sugar pot that may eventually link it directly to other fragments found at the tavern site.

Gould attributed a 13½" x 9½" (sight size) oil on paperboard Prior-Hamblen school primitive portrait to the artist George Hartwell (1815-1901). A faint pencil inscription on the back identified the subject as John Edward Holmes, then age 12, and dated the portrait to 1842. Holmes (1829-1860) was born in Stoughton, Massachusetts, and lived his entire life there, working his trade as a bootmaker. Hartwell was related to the Hamblen family by marriage. He married the daughter of Joseph Hamblen, a brother of Sturtevant Hamblen, and he often painted with William Matthew Prior. Hartwell’s works often can be distinguished by a darker red upper lip, sometimes painted with a single brush stroke, and separated from the lower lip by a thin brown line. This painting fit the criteria nicely, and at least 13 phone bidders, floor bidders, and absentee bidders pursued it to $14,950.

An early 19th-century tall clock with brass works movement had a nicely grained mahogany case with reeded quarter columns with brass footers and capitals, and a pierce-carved bonnet topped by three brass finials, with a spread-winged eagle at the peak. In the arch of the painted tombstone face was an oval gilt sunburst cameo that read “WARRENTED BY / NATH’L MUNROE / CONCORD.” Clockmaker Nathaniel Munroe (1777-1861) worked in Concord, Massachusetts, with his brother Daniel from about 1798 to 1807 and with their younger brother William as cabinetmaker. Ten years later, Nathaniel moved to Baltimore, Maryland. Given that the Munroe brothers didn’t produce a large number of clocks in Concord, $2300 didn’t seem to be too much to pay for it.

To refinish, or not to refinish: that is the question. A small blockfront Chippendale chest that had been rediscovered in a Portland, Maine, home in the 1960s had remained with the same owner until it was picked and brought to auction. The wide conforming overhung top, the dense mahogany construction, and its size, 32½" wide x 31" high x 18 1/8" deep, gave it great market appeal, but the finish showed that it had suffered centuries of benign neglect, and it evinced the effects of years of storage in an unprotected environment. Any refinishing would destroy the original surface, but as it was presented, it would be hard to image the chest in an elegant room or display setting. Perhaps the best solution would be a light oil touch-up. It sold for $17,250.

For more information, call Timothy Gould at (207) 362-6045 or visit (www.gouldauctions.com).

|

|

|

|

Originally published in the February 2015 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2015 Maine Antique Digest

Prior-Hamblen school primitive portrait of John Edward Holmes, conclusively attributed to George Hartwell, $14,950.

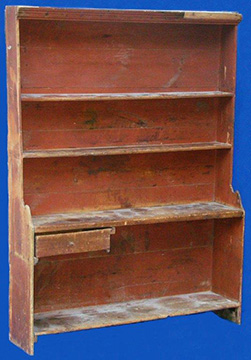

Prior-Hamblen school primitive portrait of John Edward Holmes, conclusively attributed to George Hartwell, $14,950. The early 18th-century pewter cupboard with a single drawer hanging from the bottom shelf benefited from square-nail construction, decorative stepped-back cutouts on the sides, a single piece of applied cornice trim on top, and the original rusty red surface. Complete and untouched, it found a new Maine home for $14,950. Gould photo.

The early 18th-century pewter cupboard with a single drawer hanging from the bottom shelf benefited from square-nail construction, decorative stepped-back cutouts on the sides, a single piece of applied cornice trim on top, and the original rusty red surface. Complete and untouched, it found a new Maine home for $14,950. Gould photo.