Ambrotype of Runaway Slave and Other Photos Highlight African Americana Sale

March 26th, 2015

|

The collector-agent in the U.K. who bought one of the major photography lots also bought this Louisiana slave sale broadside for $37,500 (est. $6000/9000). The 23½" x 18" announcement was printed on pink paper in 1848. It includes a detailed list of “family slaves,” i.e., house servants. There is, for example, the listing for “Nancy, aged 13 years, stout house girl, fully guarantied [sic].”

This rare cabinet card portrait of Martin Robinson Delany (1812-1885), noted abolitionist, physician, explorer, author, and proponent of Black Nationalism, realized $2750 (est. $600/800). It was published in Philadelphia in the 1870s.

A five-item lot, including this cabinet card portrait of Maria Porter, achieved $1875 (est. $400/600). Porter and her family were early members of the First Unitarian Church of Rochester, New York, which played a vital role in the lives of Rochester’s abolitionists. With her sister she founded the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society. The buyer was the University of Rochester, Wyatt Day said.

This sixth-plate ambrotype of runaway slave Elisa Greenwell sold to the National Museum of African American History and Culture for $37,500 (est. $10,000/15,000).

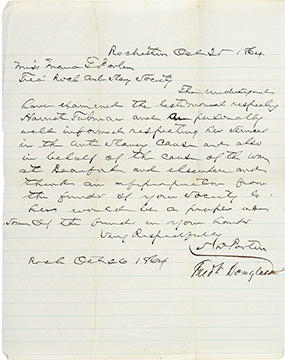

An autograph letter signed by Samuel Porter of Rochester, New York, and Frederick Douglass, attesting to the character of Harriet Tubman and requesting funds for her, sold to dealer Seth Kaller of White Plains, New York, for $40,000 (est. $7000/10,000). Addressed to Maria Porter as treasurer of the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society and dated October 26, 1864, it was described by Wyatt Day as “a blockbuster of a letter—Frederick Douglass saying that Harriet Tubman is OK in his book.” Tubman (c. 1822-1913) was an abolitionist and nurse, as well as a Union spy during the Civil War.

“Emancipated Slaves brought from Louisiana by Col. George H. Hanks,” a 5¼" x 7¾" albumen photograph on the original 8" x 10" photographer’s mount, went to a bidder overseas for $30,000 (est. $7500/10,000). It was published in New York by M.H. Kimball in 1863.

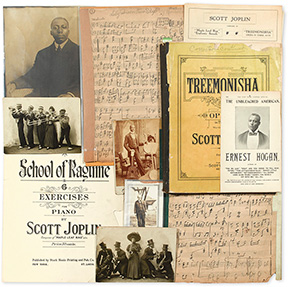

An archive of Scott Joplin and other ragtime musicians went for $50,000 (est. $7500/10,000). The consignment came from the personal collection of music historian Rudi Blesh (1899-1985). Photographs, first editions, and original manuscript copies of music were part of this important cache that went to graphic novelist Chris Ware. We e-mailed Ware about his purchase, and he kindly replied to questions. (See sidebar below.)

An 18-item lot of photographs of African American soldiers in France during World War I sold for $4750 (est. $2500/3500). They were members of the segregated 366th and 367th regiments of the U.S. Army. Average size of the images is 6½" x 8½". |

Swann Galleries, New York City

Photos courtesy Swann Galleries

Exceptional photographs were among the highlights of the latest printed and manuscript African Americana sale at Swann Galleries in New York City on March 26. A number of the best examples came from the same private collection, said Wyatt H. Day, Swann’s department expert.

A sixth-plate ambrotype of a young woman identified as a runaway slave was perhaps the most compelling image from that group. It sold for $37,500 (includes buyer’s premium) on an estimate of $10,000/15,000. The buyer, bidding in the room, represented the National Museum of African American History and Culture, scheduled to open in 2016. Its new home is under construction in Washington, D.C., on a five-acre tract adjacent to the Washington Monument. Part of the Smithsonian Institution, the museum is always a big player at these sales. The underbidder is believed to have been another institution.

The image, just 2½" x 3½", came with a slip of paper that was crucial to the lot’s value. The period handwriting on it said: “Elisa Greenwell resident of Philadelphia / runaway from the residence of / William Edelen of Leonardtown Md / in 1859.” According to Swann’s catalog, research has shown that Greenwell was born in 1830 as a slave on the plantation of William and Elizabeth Greenwell and then became the property of William Edelen, a physician and owner of a tobacco plantation in Leonardtown, Maryland, who made her the servant to his wife. By age 29, Greenwell was a free woman in the North. The story doesn’t end there, however. Records indicate that she was returned to the Edelens and ran away from them again, on March 20, 1863. How the beautiful Greenwell came to be photographed in Philadelphia in 1859 isn’t known. One longs to know the rest of her story, and that imagination factor is a primary reason why a vintage photograph like this comes to realize such an extraordinary auction result.

This image and its price may be instructively compared to a quarter-plate (3¼" x 4¼") daguerreotype that sold on November 6, 2014, at Raynor’s Historical Collectible Auctions in Burlington, North Carolina. In that case, the image was of another young and beautiful female slave—not a runaway—being hugged by the white child she was charged to care for. This image also came with an inscription: “Anna Whitridge and her faithful nurse Patty Atevis. Taken about 1848…” Anna’s name came first, because of course in the antebellum South she was considered to be the more important part of this kind of dual portrait, other examples of which are not uncommon. But it is uncommon that the identities of each could be confirmed.

According to Raynor’s, research has provided the details that Martha Ann (also known as “Patty Ann”) Atevis was born a slave circa 1816 and owned by William McCubbin of Baltimore. After McCubbin’s death in 1839, his widow sold her to another Baltimorean, John Whitridge, for $200. Atevis worked as a nurse in the Whitridge family for 36 years. Estimated at $20,000/30,000, the image of Atevis and the girl brought $18,367.50.

Both auctions were highly publicized in the photography collecting community. The same group of bidders would have known about each image. What made the price difference? Aside from the rarity of the runaway, a case could be made that, even though Greenwell was returned to slavery, she represents liberty, verve, gumption, hope, and defiance. In short, she’s a heroine. The nurse calls up an entirely different set of emotions, including shame that slavery ever even existed. The runaway makes us happy; the other, deeply sad. Which would you pay the higher price for?

Another dual portrait offered at Swann, “Old Master with favorite man servant” (a supplied title), sold to Greg French Early Photography of Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, for a mid-estimate $5000.

The quarter-plate daguerreotype from the 1850s was in its original case.

“People generally think I got a bargain, but some bidders shied away because it has wipes and scratches, which is a legitimate reaction,” French wrote me as a friend in an e-mail after the sale. “But those of us who collect nineteenth-century images realize that content can sometimes trump condition,” he added. “For me that reasoning applied to this daguerreotype.”

Observers noted the servant’s hand on the shoulder of his master. In a phone conversation after the sale, Wyatt Day said, “That is amazing, North or South, the idea of a black man touching a white man. Never heard of; it’s just not done.” In his catalog, he wrote, “There’s a definite aura of friendship and trust between these two men.” Or is there? The image’s new owner has a different view of the pose.

“There’s no doubt that sometimes familiarity can foster a relationship, and that two people living and working in close proximity can feel affection for each other,” French said. “A skeptic might say that the African American man was told to pose like this, and that he is simply the man of European descent’s possession. I’ll add that a jailor and his or her prisoner can forge a bond that transcends logistical reality. However, this daguerreotype does seem to depict a caring relationship that is genuine, even though it was formed under a terrible and inexcusable institution.”

A Civil War-era photography album of the Beals family of Stoughton, Massachusetts, sold to a dealer for $11,250 (est. $15,000/25,000). The classic oblong 19th-century book had a binding decorated with embossing and gilt. It contained 78 cartes de visite and six tintypes. All are approximately 2½" x 4". As would be expected, many were family portraits, but many others were important slavery-related images of the period. An abolitionist family would have assembled such an album.

One of the images is that of ex-slave Wilson Chinn, whose forehead was branded with his master’s initials, “V.B.M.” He is shown in a studio setting wearing an iron slave collar with prongs sticking up, meant to make escape through forest underbrush difficult or impossible. At his chained feet are other implements of punishment and torture.

Another well-known image included in the album was the notorious “Scourged Back” of Private Gordon, first name unknown. A slave on a Louisiana plantation, Gordon ran away in 1863 and went on to serve as a soldier in the U.S. Colored Troops. With his back to the camera, the crisscrossing scars made on his flesh by repeated floggings are on full display. There are variants of the same pose; all these images are considered scarce. This is in spite of the fact that the Independent, a weekly New York-based magazine that promoted abolitionism and women’s rights, encouraged its copying: “This Card Photograph should be multiplied by the 100,000 and scattered over the states. It tells the story in a way that even Mrs. Stowe cannot approach, because it tells the story to the eye.”

Perhaps the most desirable Private Gordon CDV was sold at Cowan’s Auctions on June 13, 2014, for $13,200. It bears the back mark of McPherson & Oliver, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the original makers. Another with a back mark of C. Seaver of Boston sold for $5735 on eBay in 2012.

Photos of Chinn and Gordon were sold along with others by the Freedman’s Bureau to raise money for the so-called Sanitary Fairs of the Civil War period. Private Gordon also appears in the iconic image titled “Emancipated Slaves brought from Louisiana by Col. George H. Hanks.” An albumen photograph on the original 8" x 10" photographer’s mount, it was published in 1863 and, like the cartes de visite, was used as a fund-raiser. The former slaves pictured—men, women, and children—had been set free by General Butler. The engraved version of this image appeared in Harper’s Weekly on January 30, 1864. Along with the image were biographical sketches of all the people in the photograph.

That image was offered at this sale and sold for no bargain—$30,000 (est. $7500/10,000). “We’ve had that image twice before,” said Day. “One of the copies was from my own collection. Six or eight years ago, it brought $4500 or something like that.” This one was in very good condition with very good tonal quality. Still, the price is extraordinary and, according to Day, “It’s absolutely a record.” The buyer? “A collector-agent in the U.K., who has a personal collection that he’s building, and he’s also an agent for an institution in London.”

Another remarkable image, that of a man and woman, presumably husband and wife, posed with a copy of the abolitionist newspaper the Emancipator, fetched $4500 (est. $3500/5000). The photo is a sixth-plate daguerreotype dating from the 1850s. Those in the trade say they’ve seen similar examples of abolitionists making a statement by using printed material as a prop. Day said he had seen only one. “In that case, it was a much later tintype, and the material was a book on the history of the slave trade,” he said. With high magnification, it’s possible that one could read the date of the paper—in reverse, of course.

A major lot that went unsold was a sixth-plate tintype of a three-quarter portrait of a Ku Klux Klansman in a black hooded robe with a white skull and bones on its front. The Klan was founded in Pulaski, Tennessee, in December 1865. It wasn’t until the 1920s that the robes were uniformly white. Dating from the late 1860s and estimated at a very aggressive $30,000/50,000, the image saw some action, but bidding stopped short of its reserve.

Day noted in his catalog that what are believed to be the earliest known photographic images of Klansmen are dated 1867 and 1871. These are two cartes de visite sold as a pair by Greg French a few years ago to the National Law Enforcement Museum, which is being built in Washington, D.C. As of this writing the photos could still be seen on French’s website (www.gregfrenchearlyphotography.com). Inscriptions in period ink on the reverse of each describe law enforcement’s role in apprehending them. Coincidentally, French had another tintype of a full portrait of a Klansman on his website during this sale. It was identified as originating in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Its approximate date is late 19th century. The man, wearing white robes, was posed with three weapons in his belt, two pistols and a knife. With an asking price of $8500, the image has been sold to another American museum.

This report may give the mistaken impression that KKK images are not exceedingly rare. Said French in an e-mail: “They are decidedly so. I’ve seen only the two cartes de visite I sold, the tintype I sold, the tintype at Swann’s, and another tintype in all my years”—i.e., four decades.

The two top lots of the day each went for $50,000. Neither was a photograph. One was purely words, a nearly complete manuscript copy of the Koran from the Yattara Family Library of Timbuktu, a city in what is now the West African nation of Mali. The Yattaras were one of Timbuktu’s original families, and the 17th-century copy of the central religious text of Islam came to the sale from a private collection in Mali.

At first, it didn’t seem to me that an African Americana sale was the right place to offer this item. Wouldn’t it more logically belong in a sale organized by Swann’s early books department? Yes, one would think that, Day said. “But I saw the connection clearly, because of Omar.” That is, Omar ibn Said (1770-1864), a Fulah from Senegal who was captured and enslaved and whose manuscript narrative, in Arabic, sold at Day’s very first African Americana sale at Swann March 28, 1996.

At first, it didn’t seem to me that an African Americana sale was the right place to offer this item. Wouldn’t it more logically belong in a sale organized by Swann’s early books department? Yes, one would think that, Day said. “But I saw the connection clearly, because of Omar.” That is, Omar ibn Said (1770-1864), a Fulah from Senegal who was captured and enslaved and whose manuscript narrative, in Arabic, sold at Day’s very first African Americana sale at Swann March 28, 1996.

“That is still the only known slave narrative written in the slave’s native tongue,” said Day, “and I keep stressing to people about Africa’s written culture.”

As he wrote in this sale’s catalog: “Long before the existence of Oxford or Cambridge, the scholars of the University of Sankore and other cultural centers were writing and copying thousands of manuscripts on science, astronomy, astrology, theology, mathematics, Islamic jurisprudence, and common law…. The widely held theory that sub-Saharan Africans had no written language, and therefore no recorded history, was a perfect rationale for slavery. For a couple of centuries, theologians and apologists for the slave-trade exploited this argument.”

As was Omar’s text, this Koran was written in Arabic. Its 166 leaves, each approximately 6½" x 8", were in their 17" x 8" x 2" original leather “pouch.” Part of the package was all of the necessary paperwork attesting to the authenticity of the manuscript as well as the certificates allowing the manuscript to be exported from Mali.

Still, as Day noted, “It’s a thin market,” and he sweated it out until three days before the sale when a man called him and gave him a bid of $80,000 on an estimate of $40,000/60,000. As it happened, he got it for $40,000 (hammer). “I believe he is both a buyer and an agent in the Middle East,” Day said.

An archive relating to Scott Joplin and other ragtime musicians was the other $50,000 lot. Estimated at $7500/10,000, it came from the personal collection of the late music historian Rudi Blesh and sold to Chris Ware, a well-known graphic novelist. The items include original manuscripts for several pieces of music and a number of original photographs. Many are the only known copies. One of only two known copies of Joplin’s School of Ragtime: Six Exercises for Piano, published in Cincinnati in 1908, was part of the group. Among the images was the only known photo of Arthur Marshall (1881-1968), one of Joplin’s protégés, who became his successor. The two collaborated on musical manuscripts included here, including The Lily Queen Rag.

This was a favorite lot of Day, who had a career in music before turning to rare books in the early 1980s. He worked as a researcher and cataloger for two different major New York book dealers while establishing himself as a specialist in African American studies. For the past 30 years, he has been assembling a library of rare poetry and fiction by 19th- and early 20th-century African American authors. He continues to buy, but ironically finds the prices increasingly prohibitive. “I am a victim of my own success,” he said.

For more information, phone Swann at (212) 254-4710 or see the website (www.swanngalleries.com).

|

|

|

Ware kindly sent me a scan of the two pages of Joplin’s corrections to Treemonisha, from the copy of the 1910 opera that he bought at Swann Galleries. Photo courtesy Chris Ware. |

Buyer of Ragtime Archive Talks about His Purchase

It was with unwarranted optimism that I contacted the successful bidder on one of the two $50,000 items at this sale. Getting a major buyer of anything to talk to a reporter is hardly a sure bet these days. For a variety of very good reasons, they increasingly seek anonymity. Nonetheless, when I found out that it was graphic novelist Chris Ware, I just had a feeling, based on a familiarity with his work, that he would be open enough to respond to me, and that feeling turned out to be correct.

The lot was the archive of material pertaining to Scott Joplin (1868-1917) and other ragtime musicians of the 1900-10 period of its heyday. Ware had bid by phone, so I hadn’t actually seen him in the audience, but department specialist Wyatt H. Day mentioned his name in our post-sale conversation. He hadn’t heard of him. I couldn’t immediately be sure that it was the Chris Ware but told Day that, with his permission, I was going to take a shot at making contact through the website of one of Ware’s publishers, Drawn & Quarterly (www.drawnand

quarterly.com). A dozen years ago I had interviewed that publisher for another magazine. In any case, I sent an e-mail and very shortly had a reply from Ware.

“Indeed I am [the buyer]; thank you for caring,” wrote the 47-year-old author of Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth (2002), deemed one of Amazon’s 100 Books to Read in a Lifetime in 2014. “If you’re at all interested, I’d be happy to answer two or three questions via e-mail,” offered Ware, whose most recent publication is Building Stories (2012), which was voted a top ten book of the year by the New York Times, Time, and Publishers Weekly.

Below are the questions and answers of our exchange. They offer a rare window into the passions and motivations of a true collector.

J.S.: What are your plans for the archive? It’s ordinarily the kind of thing that would go to an institution with plans for exhibition.

C.W.: Well, if someone else had won it, I would’ve hoped she or he would either publish it or somehow make it available online so that any other music researchers would have full access to it—so that’s what I’m going to do. (If any museum wanted to exhibit the materials, I’d be happy to loan them out, as well.)

J.S.: What’s your interest in Joplin and ragtime? How do Joplin and ragtime fit into your collecting interests in general? How do they fit into your career as a cartoonist/visual artist/graphic novelist? Or is your interest in this sort of ephemera entirely separate from that?

C.W.: Between 1998 and 2002 I published a magazine called the Ragtime Ephemeralist, which grew out of my childhood love for turn-of-the-century popular music as well as a more contemporary frustration with the lack of a dignified periodical for serious historical research of 19th- and 20th-century African-American music, the origins of which were more or less sanitized and swept under the peppermint-shirted rug of Post-War nostalgic reinvention of so-called Gay Nineties life. The truth is that Scott Joplin was one of America’s very greatest artists, capturing its spirit, optimism, beauty, and tragedy in every note he ever set to paper. Ragtime is also the last popular music which draws its power from composition, not performance; in other words, one can play one of Joplin’s or Joseph Lamb’s or James Scott’s pieces on a piano, a string quartet, or a string of tuned car hubcaps and still sense the emotional power. (In this, it’s not unlike comics, which are very much also an art of composition.) I started the Ephemeralist when my friend the composer Reginald Robinson noticed that a reproduced photograph of Scott Joplin’s piano seemed also to picture a fragment of a heretofore unheard piece of music, so we drove to Fisk University [in Nashville, Tennessee] in 1997 to investigate and reconstruct it from the original photograph; I published the research, and Reginald recorded the piece.

There’s no question in my mind that this archive—which originated with Rudi Blesh’s grandson, Carl Hultberg; Blesh and Harriet Janis wrote They All Played Ragtime (1950)—represents the first and basically last trove of primary source material for the period’s serious composers; the subjects they interviewed lived only a short time following the book’s publication, and Scott Joplin’s manuscripts were destroyed shortly thereafter, too—boxes of unheard material.

My good friend Rick Benjamin, who heads the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra out of Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, let me know about the auction when Ed Berlin, author of the definitive Joplin biography King of Ragtime, e-mailed him about it. (Needless to say, they’ll be the first people I send scans to.) Probably the most important part of this archive is the copy of Treemonisha, which is the same copy photographed for the republication of the work by the New York Public Library, including Joplin’s handwritten corrections on pages 166-167—which also serves as the only surviving example of his manuscript style, save the blurry photograph that Reginald noticed. This was Joplin’s personal copy of this great work, which was never produced in his lifetime. Rick spent 20 years reconstructing the orchestration for theater pit ensemble, recording it four years ago and releasing it as a book and CD (which I designed). Ed’s book is just seeing its fourth edition this fall; it’s not only “the other” great work in the world of ragtime research, along with They All Played Ragtime, but an incandescent example of how to reconstruct a life from what are, sadly, only crumbs of primary source material.

J.S.: Are you a musician on the side?

C.W.: It would be charitable to describe me that way, even with the added caveat of the phrase “on the side.” I try to play piano and finger style/classic banjo in the manner of the recording artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries such as Vess Ossman and Fred Van Eps (whose archive of manuscripts, photographs and instrument I also recently acquired, incidentally). For a while as an adolescent I was hanging around ragtime pianist Bob Darch and thought I’d even pursue it as a “career,” but, thankfully, realized I wasn’t talented enough (and that I probably also wouldn’t meet a girl playing ragtime), so I became a cartoonist instead.

Ware’s most recent comic strip, The Last Saturday, is being serialized in the Guardian. He is also an irregular contributor to The New Yorker. For more information, see Ware’s interview in the Paris Review, Fall 2014 (www.theparisreview.org/interviews/6329/the-art-of-comics-no-2-chris-ware).

Originally published in the June 2015 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2015 Maine Antique Digest

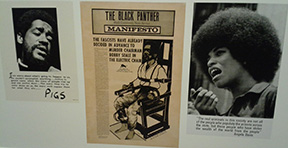

At the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam at the end of December 2014, I saw a wall of 20th-century posters and other graphics featuring radical groups working toward racial equality around the world. Many were just like ones sold over recent years at printed and manuscript African Americana sales at Swann. In fact, these examples could be the very copies. The Stedelijk is an international museum devoted to modern and contemporary art and design. For more information, see the website (

At the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam at the end of December 2014, I saw a wall of 20th-century posters and other graphics featuring radical groups working toward racial equality around the world. Many were just like ones sold over recent years at printed and manuscript African Americana sales at Swann. In fact, these examples could be the very copies. The Stedelijk is an international museum devoted to modern and contemporary art and design. For more information, see the website (