Americana at Christie’s

January 24th, 2013

|

Edward Hicks (1780-1849), Penn’s Treaty, oil on canvas, 17¾" x 23¾", with the words “Penn’s Treaty” in gold on the mahogany frame, sold for $2,546,500 (est. $600,000/900,000), the highest price of Americana Week. It has not been seen in New York since 1977 when it was shown at Hirschl & Adler. It is bold, graphic, and vibrant. Scott Webster Nolley, a Virginia conservator, wrote in the catalog that Hicks was “teaching the gospel with his paintbrush ... [and] connected the peace-making scene with the Isaiah passages depicted in the Kingdom paintings as if to illustrate the fulfillment of the prophecy.” The buyer was dealer Philip Bradley of Downingtown, Pennsylvania, underbid by Bill Samaha in the salesroom. The price was far less than the $3.6 million paid for another Hicks Penn’s Treaty just about the same size, 18" x 24", that sold at Christie’s in January 2007. At that same sale a Hicks Peaceable Kingdom, 24¼" x 30¼", sold for $6.176 million.

Silver bottle stand and glass bottles, with the Z-shaped banner mark of Thomas Fletcher and Sidney Gardiner, Philadelphia, circa 1825, together with four enamel bottle tickets marked for brandy, rye, whiskey, and bourbon. The set sold on the phone for $11,875 (est. $1500/2500).

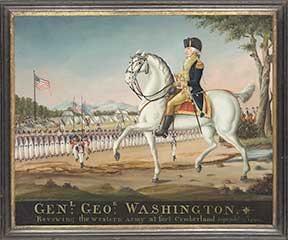

Frederick Kemmelmeyer (1755-1821), General George Washington Reviewing the Western Army at Fort Cumberland, oil on paper, 17¾" x 21¾", circa 1800, signed lower left and inscribed “Genl; Geoe; Washington./ Revewing the western army at fort Cumberland Sepembr 19th 1794” lower center, sold for $362,500 (est. $20,000/40,000). This is one of five known paintings by or attributed to Frederick Kemmelmeyer depicting George Washington reviewing the troops at Fort Cumberland. One of these paintings is at Winterthur Museum and another is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. All of the works are believed to have been painted in Baltimore before 1803. General Washington gathered his troops at Fort Cumberland on October 17 and 18, 1794, during the Whiskey Rebellion, to calm the population enraged about excise laws passed in 1791.

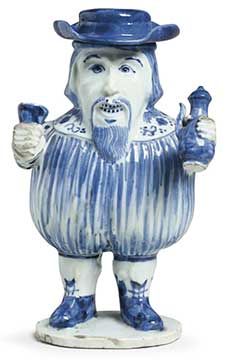

Very rare Chinese export blue and white “Mr. No-body,” late 17th century. The 8 7/8" high figure with his head and outstretched arms issuing from his ballooning breeches holds a wine ewer in one hand and a goblet in the other and wears a later removable hat. It sold to U.K. dealer Angela Howard for $158,500 (est. $40,000/60,000). Inspired by the woodcut frontispiece of the 1606 copy of the popular play by Thomas Heywood, No-body and Some-body, this lampoon figure symbolized the common man who takes the blame for everything. Becoming an iconic figure in the public’s imagination, he was made in numerous English delft examples in the ensuing decades, including one dated 1682 and now in the collection of Colonial Williamsburg. A Dutch Delft figure may have been shown to the Chinese modeler, although William Sargent suggests that a copy of the play could have made it to China on board a merchant ship, as sailors often used theatrics as a means of entertainment on their long voyages. A “Mr. No-body” in the Mottahedeh collection was sold at Sotheby’s on October 19, 2000, for $64,000; it is now in the collection of the Peabody Essex Museum and is illustrated in China for the West (1978) by David Howard and John Ayers and also appears in W.R. Sargent’s Treasures of Chinese Export Ceramics (2012). Additional examples are in the Groninger Museum and in the the Victoria and Albert Museum from the Ionides collection.

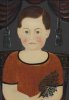

There were three phone bidders and bidders in the salesroom for this portrait of a woman with a bowl of cherries. The 25" x 19¼" oil on panel sold on the phone for $80,500 (est. $5000/10,000). It also came from the Swiss bank vault along with the Penn’s Treaty, the Kemmelmeyer, and the Grandma Moses.

Queen Anne carved maple armchair attributed to John Gaines III (1704-1743), Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1735-43, 42" high, sold for $542,500 (est. $200,000/300,000) to dealer Todd Prickett of Yardley, Pennsylvania, underbid by dealer Bill Samaha. Called the “most impressive and important survivor of the work of John Gaines III,” it stands (along with an example at the Metropolitan Museum of Art) as one of only two armchairs that can be assuredly assigned to John Gaines III. The most arresting feature of the chair is its large out-sweeping ram-horn arms. Their large size differentiates Gaines’s versions from others.

Chinese export blue and white “Europa and the Bull” coffeepot and cover, early 18th century, octagonal with bun feet in European silver form, decorated with a western landscape showing hunters beneath an elaborate border enclosing the mythological scene, 11½" high, sold on the phone for $32,500 (est. $15,000/25,000). Christiaan J.A. Jorg and Jan van Campen illustrate an example in Chinese Ceramics in the Collection of the Rijksmuseum alongside a Delft prototype, also based on a silver model, noting that this form was an early Chinese response to the new fashion of drinking coffee that had arrived in Europe in the late 17th century. Another (restored) example was in the Ionides collection and then the Mottahedeh collection and sold at Sotheby’s on October 19, 2000, for $10,800. The difficulty of achieving this form soon led to its replacement by smooth-sided conical pots with simpler spouts and handles and flat bases. |

New York City

Photos courtesy Christie’s

In the Super Bowl of Americana auctions that took place during the third week of January, Christie’s was the winner in the annual match-up with Sotheby’s. The score was 15 to 10, or, to be exact, $15,008,200 to $9,976,830. Presale estimates, figured without buyers’ premiums, at Christie’s were $7.6/11.5 million; Sotheby’s presale expectations were $11/18.4 million.

Christie’s won with a leaner, more carefully edited sale. Of the 404 lots offered on January 24, 25, and 28, Christie’s sold 338; that is 83.7%. There were some fumbles in silver and needlework. Sotheby’s offered 639 lots and sold 443 lots or 69.3% of what was offered.

More people want to sell Americana in New York City in January than at any other time of the year because of the annual pilgrimage of Americana collectors to Manhattan for the shows, lectures, parties, and sales. The sale previews were very well attended. Dealers and their clients, curators, and conservators turn furniture upside down, shine their flashlights on dovetails, remove moldings and table tops, use black lights on paintings to look for inpainting, and read endless condition reports before they decide what to buy.

The auctioneers compete first for the consignments and then present histories in heavy, well-illustrated catalogs. Christie’s offered two discoveries: a Newport, Rhode Island, four-shell bureau table and a tiny porcelain bowl made by John Bartlam in South Carolina. Bartlam is now considered the first to make porcelain in America.

The Newport kneehole bureau sold for $2,210,500 (est. $700,000/900,000) despite the fact that its feet had lost 4". The fact that a pencil signature was found on the top drawer helped even though it was misread at first and is not as described in the catalog. Andrew Holter and John Hays of Christie’s thought it read “John Townsend 1767.” John Townsend was Newport’s best-documented cabinetmaker and the subject of a Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition and catalog by Morrison Heckscher in 2005.

When Yale’s Patricia Kane, who for the last decade has been leading the study of Newport furniture at the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at Yale University Art Gallery, looked at the drawer bottom she saw the name “Jonathan,” John’s younger brother who worked in his shop until he died in 1773. An infrared photograph turned up a second date and signature, much smaller, that John Hays said reads “John [smudge] finished 1767.”

Martha Willoughby, who wrote the catalog entry, said she did not see the piece in person until she arrived in New York City from England, and she was not sure she could make out the name John Townsend, but she said the date 1767 was written a second time. The pencil signatures on Townsend furniture are thought to be earlier than the paper labels John Townsend ordered as he prospered. Moreover, the color of this kneehole bureau was richer than the labeled John Townsend kneehole bureau dated 1765 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and its top was made of a mahogany board with the same dramatic grain. The fact that it was a discovery, unknown and unpublished until now, and consigned by descendants of the Pell and Coster families, who could have owned it in the 18th century, made it the most talked-about piece of furniture during Americana Week. There was bidding for it in the salesroom, on line, and on the phones. The buyer, said to be a young collector, was on the phone with Willoughby.

The most talked-about piece of porcelain was the tiny tea bowl made by John Bartlam at Cain Hoy near Charlestown, South Carolina. It was making its first appearance at auction. It was sent from England, where three other identical bowls were found, and was offered during the furniture and folk art session on Friday morning, January 25. There was keen competition for it, and it sold for $146,500 (est. $30,000/50,000) to dealer Bill Samaha of Massachusetts for a client who will probably put it on view at a museum. The underbidder was curator John Stuart Gordon from Yale University. “It is such a great teaching object,” he said, clearly disappointed. The price makes the curators at Chipstone in Milwaukee and the Philadelphia Museum of Art look very smart to have acquired their Bartlam bowls for much less, said to be between $50,000 and $75,000. Let’s hope the fourth one, still owned in England, goes to the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), which encouraged the original studies that uncovered the story of Bartlam’s porcelain factory at Cain Hoy.

Of the ten tray-top tea tables offered in New York City during Americana Week, Christie’s had the most coveted, and Todd Prickett bought the Boston tea table with candle slides for $962,500 (est. $600,000/800,000). It was underbid by a young man standing at the back of the salesroom taking bidding signals from his father, who was seated on an aisle and was bidding when he tugged his ear lobe. At the Eddy Nicholson sale in 1995, Christie’s sold this table for $552,500. The underbidder bought another Boston tray-top tea table with a drawer and a scalloped skirt for $290,500; it had sold at Christie’s in 2003 for $436,000 and at Sotheby’s in 2007 for $385,000.

The captioned pictures show that most, but not all, furniture sold this January brought less in 2013 than in the past. An exception was the Federal white-painted and parcel-gilt églomisé girandole wall clock, one of only 30 known clocks by Lemuel Curtis, that sold for $578,500 (est. $60,000/90,000) even though its original spread-wing American eagle finial was missing. The eagle was on it when it sold at Sotheby’s in June 1992 for $154,000. The clock descended in the Whipple family of Salem.

Christie’s has been selling choice pieces of furniture from WEA Enterprises, the engineering and real estate business of New York collector Martin Wunsch. This time it was a Queen Anne maple armchair attributed to John Gaines “at his best” with arms ending in flaring ram’s horn terminals. It sold for $542,500 to Samaha.

Christie’s also offered two early collections that have been off the market for a generation—one of folk art and the other needlework—which made the sale seem fresh. A group of folk paintings from a Swiss bank vault included Penn’s Treaty by Edward Hicks, which sold for $2,546,500, the highest price of the week. The vault also included one of five known paintings by Frederick Kemmelmeyer (1755-1821) of General George Washington reviewing the western army at Fort Cumberland on September 19, 1794, during the Whiskey Rebellion. It sold on the phone for $362,500. There also was an early 18th-century portrait on panel of a woman with cherries that sold for $80,500 (est. $5000/10,000), and some lesser works sold for well under $10,000; all were bought in the late 1970’s.

The collection of needlework did not do as well as the folk art. Eleven of the 24 samplers offered failed to sell, mostly because of poor condition.

The best-documented and most-admired of the schoolgirl samplers was by Nancy Winsor. It was stitched at Miss Balch’s school in Providence, Rhode Island, and depicted ships and people in a pastoral scene. Betty Ring wrote about it. She found letters from Nancy’s father, who regularly wrote to Balch about his daughter’s education. The needlework sold on the phone for $110,500 (est. $80,000/120,000). It was considered a good buy.

A needlework on linen of a map of the United States with the names of 22 states and five Great Lakes, possibly worked by Agness M. Candlish of Virginia, sold for $52,500 (est. $12,000/18,000) to a Virginia institution.

Who said people are not entertaining anymore? Christie’s got $182,500 (est. $70,000/100,000) for a Chinese export porcelain Orange Fitzhugh armorial dinner service, 1805-10, and $98,500 (est. $50,000/80,000) for an extensive Tiffany & Co. silver flatware service in the Chrysanthemum pattern that came in a fitted chest.

On January 24 Christie’s sales began with silver, which contributed $1,181,675 to the total, with 49 of the 59 lots offered sold. Silver was 83% sold by lot and 76% by value. The Tiffany Viking bowl, however, failed to sell (est. $100,000/150,000), and a set of three silver casters by Simeon Soumaine, circa 1750, with the same estimate, got no bids. Two phone bidders competed for a Paul Revere drum-shaped teapot engraved with the initials “CC.” It sold for $230,500 (est. $150,000/250,000). A set of six silver canns with heraldic engraving, consigned by the Tabernacle Congregational Church, United Church of Christ, in Salem, Massachusetts, sold for $79,300 (est. $50,000/80,000). A silver tankard with a clear mark of John Edwards, Boston, circa 1710, sold for $21,250 (est. $5000/8000) to dealer Jonathan Trace of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Sales of English pottery and Chinese export porcelain ended the week on January 28. Most of the English salt-glazed creamware came from the estate of William Burton Goodwin and had been on loan to the Portland Museum of Art in Maine for the last 20 years. Some pieces were not in good condition, and some were repainted, but there was competition on a few lots, and others seemed like real bargains. The first lot, two salt-glazed stoneware teapots, a pear-shaped milk jar, and a tea bowl, sold reasonably for $3500 (est. $4000/6000), but a rare glazed redware camel teapot with the howdah strapped on its back and scenes of a standing camel under a palm sold for $11,250 (est. $6000/8000) to dealer Garry Atkins of London. A salt-glazed camel teapot sold for $7500 on the phone. Atkins also paid $15,000 for an agate pecten-shell teapot (est. $5000/7000) and the same price (est. $7000/9000) for a cauliflower coffeepot, 1760-70. No one wanted English delft blue-dash chargers with images of English kings and queens, but Atkins paid $110,500 (est. $50,000/70,000) on behalf of an American institution for a London delft plate illustrating the story of Abraham and Isaac.

Chinese export porcelain accounted for $2,982,400 and was 91% sold by lot and 96% by value. A pair of fish bowls painted with scenes showing the production of porcelain sold on the phone for $266,500 (est. $100,000/150,000). A very rare Mr. No-body figure, a Chinese copy of a Dutch Delft form, sold for $158,500 (est. $40,000/60,000) to dealer Angela Howard of the U.K. in the salesroom. The consignor, in the salesroom, said he bought it from Mildred Mottahedeh in 1970 for $2500 and that he would give the proceeds to the Salvation Army. A punch bowl of Philadelphia interest with a William Birch view of the Waterworks Pump House at Center Square on the front and back, depictions of the U.S.S. Constitution and the H.M.S. Guerriere on the sides, and grisaille fish inside, perhaps a reference to Fish House Punch, sold to the trade for $134,500. Two plates of historical interest sold above estimates. A Society of the Cincinnati plate, circa 1785, from the service bought by Henry “Light- Horse Harry” Lee for George Washington, sold for $98,500 (est. $25,000/40,000), and one of Martha Washington’s “States” dishes, circa 1795, sold for $86,500 (est. $20,000/40,000).

Participation of Chinese bidders in the salesroom pushed the price of some blue and white wares well over estimates, and they bought other lots within estimates. Several were active buyers. One Chinese woman bought several large baluster jars, paying $56,250 (est. $30,000/50,000) for a pair of Famille Rose jars; $17,500 (est. $8000/12,000) for a single jar; and $35,000 (est. $12,000/18,000) for a pair of gilt-decorated baluster vases with Buddhist lion knops. Christie’s sales ended the week on an up note.

The pictures and captions give more details. Andrew Holter, head of American furniture and decorative arts, said he was encouraged. “There was good attendance at the preview and at the sales and competitive bidding from relatively new collectors as well as the old stalwarts,” he said. The next Americana sale at Christie’s will be on September 25.

For more information, contact Christie’s at (212) 636-2000 or on line at (www.christies.com).

|

|

|

Found in a New York City apartment on an estate appraisal, this four-shell bureau table was made in the shop of John Townsend where his younger brother, Jonathan, worked until he died in 1773. Christie’s John Hays believes that John Townsend (1733-1809) of Newport, cabinetmaker and master of block-and-shell ornament, also wrote his name and the date 1767 on the bottom of the top drawer to the right of his brother’s large scrawled signature and date. Martha Willoughby was not as certain when she examined the infrared photograph, but there was no doubt the bureau came from the John Townsend shop. The four-shell forms, more expensive options to the design, with an arched rather than a shell-carved cabinet door, “represent the epitome of John Townsend’s best work,” according to Morrison Heckscher, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s curator of the American Wing and author of the catalog accompanying the exhibition of work by John Townsend in 2005. The distinctive graphite signature appears on the underside of the top drawer, making this piece one of only two known bureau tables bearing John Townsend’s autograph and the only one with Jonathan’s signature. Early in his career John Townsend signed his furniture; later he used signed and then printed labels. Townsend’s graphite signature appears on seven other pieces, six of which—two high chests, a document cabinet, a dining table, and two card tables—are known to predate 1770. That these signatures were meant to be seen is indicated by their size and prominent locations. Three other full-size case pieces are signed in large script in pencil on drawer bottoms. Construction details show the bureau was made early in Townsend’s career. This bureau table displays all the details seen on 1765 examples, except for its use of a “bow-tie” key in the joinery of the top, a modification made by Townsend to his formula for cabinetwork construction, now here documented in use in 1767. The brasses on this bureau have their original surface and retain much of their first coating, an organic varnish that was baked on to the plates when they were manufactured in Birmingham, England. This coating is evident in the greenish-hued areas and may have contained a tinted pigment, which being fugitive is no longer apparent. That the coating survives on these brasses is a remarkable occurrence as such flat surfaces were invariably cleaned and polished. Like his cabinetwork, the brasses chosen by John Townsend to adorn case pieces display little variation. |

|

Three other such tea bowls are known, two in public collections, the third in a private collection. The first to be identified was acquired by the Chipstone Foundation in Milwaukee through dealer Roderick Jellicoe. Its attribution and acquisition was heralded by Robert Hunter in his article for the January/February 2011 issue of The Magazine Antiques and subsequently celebrated at the November 2011 meeting in Milwaukee of the American Ceramics Circle. Another was sold to the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the fall of 2012 for $75,000; the consignor did not want to risk auction. All four extant examples of Bartlam’s work originated in English collections, through the dealer Jupiter Antiques, which sold them as Isleworth, an obscure English pottery. How did they get to England? Some said Bartlam could have brought them back. Others hope to find a bill of lading showing that Bartlam shipped porcelain from Charleston for sale in London. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Originally published in the April 2013 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2013 Maine Antique Digest

Rare Chinese export “Philadelphia” punch bowl, circa 1815, painted front and back in sepia with Benjamin Latrobe’s 1799 Waterworks Pump House, once at Center Square, Philadelphia, and the sides showing two views of the War of 1812 of the engagement between the U.S.S. Constitution and the H.M.S. Guerriere; the interior is decorated with three grisaille fish. The bowl is 13 3/8" in diameter and sold on the phone to the trade for $134,500 (est. $20,000/30,000). This apparently unique and unrecorded punch bowl has strong Philadelphia associations and must have been commissioned by a member of one of the leading China trade families of that city. The 1799 Pump House at Center Square was designed by Benjamin Latrobe, founder of professional architecture in America. Another source of pride for Philadelphia, as for the entire nation, was the success of the U.S.S. Constitution in the War of 1812. Her August battle with H.M.S. Guerriere earned her the “Old Ironsides” nickname; the British ship was so damaged that it was destroyed by American Captain Isaac Hull. The fish decorating the interior of this bowl are exact duplicates of those on the famed Schuylkill Fishing Company bowl. Considered the oldest private club in America (and birthplace of “Fish House Punch”), the Fishing Company commissioned its massive punch bowl in 1812 under its longtime governor, “Capt.” Samuel Morris. Charles Ross brought that bowl back on the Caledonia in 1812. He was the supercargo on the voyage, his third to China, and part owner of the ship. Ross also presented two Mandarin hats to the club, where they remain; the following year he was made a member.

Rare Chinese export “Philadelphia” punch bowl, circa 1815, painted front and back in sepia with Benjamin Latrobe’s 1799 Waterworks Pump House, once at Center Square, Philadelphia, and the sides showing two views of the War of 1812 of the engagement between the U.S.S. Constitution and the H.M.S. Guerriere; the interior is decorated with three grisaille fish. The bowl is 13 3/8" in diameter and sold on the phone to the trade for $134,500 (est. $20,000/30,000). This apparently unique and unrecorded punch bowl has strong Philadelphia associations and must have been commissioned by a member of one of the leading China trade families of that city. The 1799 Pump House at Center Square was designed by Benjamin Latrobe, founder of professional architecture in America. Another source of pride for Philadelphia, as for the entire nation, was the success of the U.S.S. Constitution in the War of 1812. Her August battle with H.M.S. Guerriere earned her the “Old Ironsides” nickname; the British ship was so damaged that it was destroyed by American Captain Isaac Hull. The fish decorating the interior of this bowl are exact duplicates of those on the famed Schuylkill Fishing Company bowl. Considered the oldest private club in America (and birthplace of “Fish House Punch”), the Fishing Company commissioned its massive punch bowl in 1812 under its longtime governor, “Capt.” Samuel Morris. Charles Ross brought that bowl back on the Caledonia in 1812. He was the supercargo on the voyage, his third to China, and part owner of the ship. Ross also presented two Mandarin hats to the club, where they remain; the following year he was made a member. Yale’s Patricia Kane found that the signature on the bottom of a drawer of this carved mahogany block-and-shell bureau table, Newport, circa 1770, was not “John Townsend” as cataloged but his younger brother, Jonathan Townsend. The bureau table appears to retain its original brasses, but the lower sections of the foot brackets are replaced. Measuring 32½" high x 36½" wide x 20" deep, it sold on the phone for $2,210,500 (est. $700,000/900,000). Christie’s said the buyer is a young private collector.

Yale’s Patricia Kane found that the signature on the bottom of a drawer of this carved mahogany block-and-shell bureau table, Newport, circa 1770, was not “John Townsend” as cataloged but his younger brother, Jonathan Townsend. The bureau table appears to retain its original brasses, but the lower sections of the foot brackets are replaced. Measuring 32½" high x 36½" wide x 20" deep, it sold on the phone for $2,210,500 (est. $700,000/900,000). Christie’s said the buyer is a young private collector. This porcelain tea bowl made by John Bartlam, 1765-70, at Cain Hoy, South Carolina, sold for $146,500 (est. $30,000/50,000) to dealer Bill Samaha for a client. Printed in the “Bartlam on the Wando” pattern, it has two seaside vignettes, one with a figure on a fretwork bridge, pine trees, and rockwork at the right and two figures in a boat at the left; the other with a house below a cliff, a sailing ship at the right. On the bottom of the interior is an islet with a palm tree. The fretwork band edging the rim is hand painted. Measuring 1 5/8" high x 3 1/8" diameter, this little bowl was underbid by John Stuart Gordon, a curator at Yale Art Museum. The printed chinoiserie vignettes, with one that mysteriously includes a palm tree, can be confirmed through archaeological evidence matching shards found at Cain Hoy, the site of Bartlam’s short-lived factory. Scientific analysis of the clay confirms that it was made at the factory operated by the Staffordshire potter John Bartlam at Cain Hoy, outside of Charleston, South Carolina, 1765-70. It is the first porcelain manufactured in America. No longer is Philadelphia’s Bonnin & Morris the first American porcelain.

This porcelain tea bowl made by John Bartlam, 1765-70, at Cain Hoy, South Carolina, sold for $146,500 (est. $30,000/50,000) to dealer Bill Samaha for a client. Printed in the “Bartlam on the Wando” pattern, it has two seaside vignettes, one with a figure on a fretwork bridge, pine trees, and rockwork at the right and two figures in a boat at the left; the other with a house below a cliff, a sailing ship at the right. On the bottom of the interior is an islet with a palm tree. The fretwork band edging the rim is hand painted. Measuring 1 5/8" high x 3 1/8" diameter, this little bowl was underbid by John Stuart Gordon, a curator at Yale Art Museum. The printed chinoiserie vignettes, with one that mysteriously includes a palm tree, can be confirmed through archaeological evidence matching shards found at Cain Hoy, the site of Bartlam’s short-lived factory. Scientific analysis of the clay confirms that it was made at the factory operated by the Staffordshire potter John Bartlam at Cain Hoy, outside of Charleston, South Carolina, 1765-70. It is the first porcelain manufactured in America. No longer is Philadelphia’s Bonnin & Morris the first American porcelain. Queen Anne mahogany tea table with slides, Boston, 1740-60, 26¾" high x 30" wide x 18¾" deep, sold for $962,500 (est. $600,000/800,000) to dealer Todd Prickett of Yardley, Pennsylvania, underbid by a collector in the salesroom. This table, a rare survival, is of the most highly developed form of Queen Anne tea tables made in 18th-century Boston with its pinched cornered top, fluidly carved cyma-shaped apron, and pad-foot cabriole legs, and the rare embellishments of carved C-scrolls and candle slides. This table was once owned by Levi Lincoln, a Revolution-era patriot and self-made statesman who served as governor of Massachusetts from 1808 to 1809.

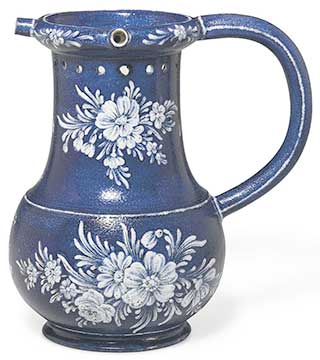

Queen Anne mahogany tea table with slides, Boston, 1740-60, 26¾" high x 30" wide x 18¾" deep, sold for $962,500 (est. $600,000/800,000) to dealer Todd Prickett of Yardley, Pennsylvania, underbid by a collector in the salesroom. This table, a rare survival, is of the most highly developed form of Queen Anne tea tables made in 18th-century Boston with its pinched cornered top, fluidly carved cyma-shaped apron, and pad-foot cabriole legs, and the rare embellishments of carved C-scrolls and candle slides. This table was once owned by Levi Lincoln, a Revolution-era patriot and self-made statesman who served as governor of Massachusetts from 1808 to 1809. Staffordshire salt-glazed, enameled blue-ground stoneware puzzle jug, 1755-60, with white enameled “L” mark, attributed to William Littler, possibly in partnership with Aaron Wedgwood. The 6¾" high pear-shaped jug is pierced with a band of circlets below the rim and is enameled in white and blue with bouquet and foliate sprays. The tubular handle is attached to the hollow rim set with three spouts. It sold in the salesroom unreserved for $8125 (est. $10,000/15,000) to an agent for a collector. It is the only example of this form and type extant. According to the catalog, a Littler blue teapot and cover from Bernard and Judith Newman’s collection sold at Sotheby’s on January 21, 2005, for $48,000.

Staffordshire salt-glazed, enameled blue-ground stoneware puzzle jug, 1755-60, with white enameled “L” mark, attributed to William Littler, possibly in partnership with Aaron Wedgwood. The 6¾" high pear-shaped jug is pierced with a band of circlets below the rim and is enameled in white and blue with bouquet and foliate sprays. The tubular handle is attached to the hollow rim set with three spouts. It sold in the salesroom unreserved for $8125 (est. $10,000/15,000) to an agent for a collector. It is the only example of this form and type extant. According to the catalog, a Littler blue teapot and cover from Bernard and Judith Newman’s collection sold at Sotheby’s on January 21, 2005, for $48,000. Federal white-painted and parcel-gilt églomisé girandole wall clock, signed by Lemuel Curtis (1790-1857), Concord, Massachusetts, 1816-22, with églomisé paint work probably by Benjamin B. Curtis (1795-1860), Boston; the front plate of the movement is stamped “L. CURTIS” within a cartouche, and the glass throat panel is stenciled “L. CURTIS”; the interior of the backboard and frames for the two doors and throat panel are each marked III with curved gouges. Measuring 40½" high x 13" wide x 4¾" deep, it sold for $578,500 (est. $60,000/90,000), even though the eagle final was missing. When it was pictured on the front cover of Sotheby’s June 19, 1992, sale catalog it had its original eagle, and it sold for a then hefty $154,000 to Jack Warner for the Westervelt Company collection. It has been hailed as America’s most beautiful timepiece.

Federal white-painted and parcel-gilt églomisé girandole wall clock, signed by Lemuel Curtis (1790-1857), Concord, Massachusetts, 1816-22, with églomisé paint work probably by Benjamin B. Curtis (1795-1860), Boston; the front plate of the movement is stamped “L. CURTIS” within a cartouche, and the glass throat panel is stenciled “L. CURTIS”; the interior of the backboard and frames for the two doors and throat panel are each marked III with curved gouges. Measuring 40½" high x 13" wide x 4¾" deep, it sold for $578,500 (est. $60,000/90,000), even though the eagle final was missing. When it was pictured on the front cover of Sotheby’s June 19, 1992, sale catalog it had its original eagle, and it sold for a then hefty $154,000 to Jack Warner for the Westervelt Company collection. It has been hailed as America’s most beautiful timepiece. This London delft polychrome dish, circa 1660, 13¾" diameter, is painted with a depiction of Abraham and Isaac. Isaac kneels in prayer on a pyre while the Angel of the Lord appears in the clouds to prevent Abraham from sacrificing Isaac with his sword. The pair is flanked by trees, and a boiling cauldron is to one side. The underside is covered in a cream slip with a slightly green lead glaze. It sold to London dealer Garry Atkins for $110,500 (est. $50,000/70,000). Atkins was bidding for an American institution. Both the palette and drawing of this dish are extremely unusual. The trees appear to have their foliage trekked or pounced in blue. The painter also had difficulty in placing the subject, as a ghost outline can be discerned that was an earlier attempt in underglaze blue. The glassy lead glaze appears to be laid on top of a white tin-glazed slip with a startlingly vibrant effect. The form of the dish, exceptionally shallow, is also extremely unusual.

This London delft polychrome dish, circa 1660, 13¾" diameter, is painted with a depiction of Abraham and Isaac. Isaac kneels in prayer on a pyre while the Angel of the Lord appears in the clouds to prevent Abraham from sacrificing Isaac with his sword. The pair is flanked by trees, and a boiling cauldron is to one side. The underside is covered in a cream slip with a slightly green lead glaze. It sold to London dealer Garry Atkins for $110,500 (est. $50,000/70,000). Atkins was bidding for an American institution. Both the palette and drawing of this dish are extremely unusual. The trees appear to have their foliage trekked or pounced in blue. The painter also had difficulty in placing the subject, as a ghost outline can be discerned that was an earlier attempt in underglaze blue. The glassy lead glaze appears to be laid on top of a white tin-glazed slip with a startlingly vibrant effect. The form of the dish, exceptionally shallow, is also extremely unusual. Rare Chinese export “Order of the Cincinnati” plate, 9½" in diameter, circa 1785, decorated with a hovering angel blowing a trumpet and suspending the badge of the Society of the Cincinnati, within a molded scalloped rim, sold on the phone to a private collector for $98,500 (est. $25,000/40,000). It had a hairline crack and some wear. It is from the famed service purchased by Colonel Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee for George Washington in New York in 1786. Sixty-six pieces of the service are at the Winterthur Museum. The insignia of the Society of the Cincinnati (founded in 1783 at the suggestion of Major General Henry Knox, inspired by the Roman farmer turned patriot/soldier Cincinnatus) was designed by Major Pierre L’Enfant, featuring the bald eagle, which had just been adopted by Congress as the new nation’s seal. Orders for Chinese porcelain featuring Cincinnati decoration were organized by founding member Major Samuel Shaw, supercargo on the Empress of China and former aide-de-camp to General Knox. According to catalog notes, the figure that suspends the badge on this service is a combination of two elements seen on the society’s membership certificate: an allegorical female figure shown near the center of the certificate, who is turning her head back over her shoulder, and the putto at right with the trumpet of fame.

Rare Chinese export “Order of the Cincinnati” plate, 9½" in diameter, circa 1785, decorated with a hovering angel blowing a trumpet and suspending the badge of the Society of the Cincinnati, within a molded scalloped rim, sold on the phone to a private collector for $98,500 (est. $25,000/40,000). It had a hairline crack and some wear. It is from the famed service purchased by Colonel Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee for George Washington in New York in 1786. Sixty-six pieces of the service are at the Winterthur Museum. The insignia of the Society of the Cincinnati (founded in 1783 at the suggestion of Major General Henry Knox, inspired by the Roman farmer turned patriot/soldier Cincinnatus) was designed by Major Pierre L’Enfant, featuring the bald eagle, which had just been adopted by Congress as the new nation’s seal. Orders for Chinese porcelain featuring Cincinnati decoration were organized by founding member Major Samuel Shaw, supercargo on the Empress of China and former aide-de-camp to General Knox. According to catalog notes, the figure that suspends the badge on this service is a combination of two elements seen on the society’s membership certificate: an allegorical female figure shown near the center of the certificate, who is turning her head back over her shoulder, and the putto at right with the trumpet of fame. A very rare Chinese export “Lady Washington States” dish, circa 1795, with the initials “MW” within a sunburst above a red banner inscribed “Decus Et Tutamen Ab Illo,” the rim encircled with the names of the 15 states in a chain linked by gilt rings and enclosed by a thin blue snake biting his tail. Measuring 8 1/8" wide, it sold for $86,500 (est. $20,000/40,000) to the Mount Vernon Ladies Association. Martha Washington’s “States” tea service was presented to her by Andreas van Braam Houckgeest, who arrived at the port of Philadelphia in April 1796 on his chartered ship the Lady Louisa and recorded in its ledgers a “Box of China for Lady Washington.” The original order delivered to Mrs. Washington is believed to have included 45 pieces, 22 of which were recorded by J.G. Lee in 1984 as in public collections. Recently, shards from the service have been excavated at Mount Vernon, further diminishing the possible number of pieces left in private collections.

A very rare Chinese export “Lady Washington States” dish, circa 1795, with the initials “MW” within a sunburst above a red banner inscribed “Decus Et Tutamen Ab Illo,” the rim encircled with the names of the 15 states in a chain linked by gilt rings and enclosed by a thin blue snake biting his tail. Measuring 8 1/8" wide, it sold for $86,500 (est. $20,000/40,000) to the Mount Vernon Ladies Association. Martha Washington’s “States” tea service was presented to her by Andreas van Braam Houckgeest, who arrived at the port of Philadelphia in April 1796 on his chartered ship the Lady Louisa and recorded in its ledgers a “Box of China for Lady Washington.” The original order delivered to Mrs. Washington is believed to have included 45 pieces, 22 of which were recorded by J.G. Lee in 1984 as in public collections. Recently, shards from the service have been excavated at Mount Vernon, further diminishing the possible number of pieces left in private collections.