Haeger Potteries Auction

February 24th, 2017

Leslie Hindman Auctioneers, Chicago, Illinois

Photos courtesy Leslie Hindman Auctioneers

Deciding to close Haeger Potteries in 2016 after 145 years was a difficult decision for Alexandra Haeger Estes, great-granddaughter of the founder of the East Dundee, Illinois-based company, but it was eased somewhat by watching people line up for the remaining pieces and having them tell her stories about vases or other vessels that had been in families for generations.

“We couldn’t compete any longer with all the things flooding the market from the Pacific Rim,” Estes said. “In the early days, the quality [of the knockoffs] was not the same, but as time went on, the quality became quite adequate for most people.”

For decades, she said, “Our designs fit people’s décor and colors. They were comfortable and pretty useful...the kind of thing that fit into a home. They were handed down and handed down, helping people realize that there were not just machines banging these out; yes, it was mechanized, but more handmade than machine-made.”

The sprawling factory, where a number of high-profile designers created up to 50 new products a year, pioneered glazes, and mentored young ceramicists, has been sold to a company that manufactures film and plastic bags. Haeger’s museum, containing what was once the world’s largest vase and other special pieces, also was closed, and some 2000 Haeger items were auctioned at Leslie Hindman Auctioneers in Chicago on February 24.

Advertised as a sale of part of Chicago-area history, it was an online-only auction with 217 lots, only relatively few of which drew spirited bidding. Almost without exception, the pieces drawing interest were standouts in design, function, or decoration, distinctly different from the more practical and now-dated colors of Haeger’s standard production.

As many as 30 lots were passed, though some sold after the sale, and other lots of three, five, or more pieces sold once the opening minimums were dropped as the sale progressed. Works signed by or attributed to designers Harding Black and Sebastiano Maglio did well, as did such signature Haeger figures as panthers in brilliant black, gold, and even unglazed.

The vases, lamp bases, table articles, and the like that sustained Haeger for decades because they were affordable and contemporary for average people, if not arty enough for many collectors, were abundant in the auction, probably to their downfall.

Collector John Magon of Madison, Wisconsin, successfully bid for a large abstract sculpture, but he lamented the many unsold lots. He said he has about 80 Haeger pieces and regularly extols the virtues of the pottery to those less knowledgeable.

An unusual 32½" tall abstract sculpture that collector John Magon researched before securing for $409.50 was probably a prototype by a designer nurtured at Haeger.

He wanted to start collecting and loved the look of Bakelite but couldn’t afford it. “I thought there must be something out there in my budget,” Magon said, and what he initially found was a Haeger stalking panther anchoring a planter. “I fell in love with the pottery line.”

Magon quickly discovered that Haeger was “the stepchild in the collecting world. Everybody knew them for pots, but then they saw things from my collection.... They didn’t know they made all these figures.”

“They cranked out hundreds and hundreds of things. Haeger just makes you smile,” Magon said.

He believes the sculpture that he bought at the sale for $409.50 (including buyer’s premium) was hand thrown, a rarity for Haeger, by Marvin Zehnder, who worked in Michigan before signing on with Haeger in the 1960s. It likely was a prototype and never put into production, making it all the more interesting to Magon, who’s considering writing a book based on his research into the piece.

Besides crafting a wide range of ceramic pieces, designer Royal Hickman worked in Mexican silver. This group of coffee and tea articles carrying his mark sold for $1250.

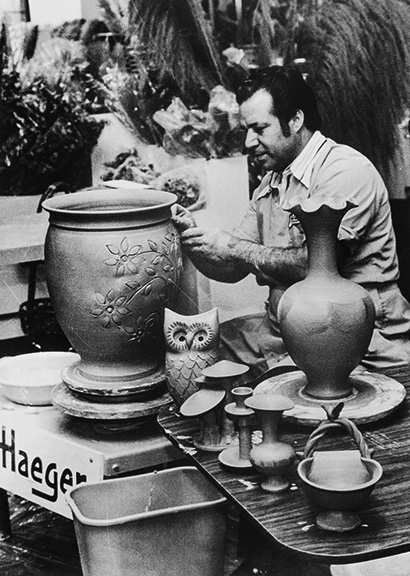

The best known of a line of Haeger designers included Royal Hickman, who introduced the stalking panther in 1941; Eric Olsen, best known for his vivid red bull figures and sculptural busts of prominent figures of the time; Sebastiano Maglio, hired in 1963 largely because of his wheel-throwing prowess, which he showed off regularly in factory demonstrations; and Harding Black, who originally was a painter. C. Glenn Richardson worked for Haeger for 20 years, until 1991, creating items that ranged from animal figures to sculpted architectural forms.

After the sale’s first lot, a 1914 vase, was passed (it later sold for $93.75 against an estimate of $150/250), Hickman’s 15¾" high perched parrot sold for $409.50, double its $100/200 estimate. A cylindrical vase signed “Hick 39,” featuring a mermaid emerging from flowers, drew considerable pre-auction interest, said sale organizer Cassia Baker, even though several flower stems were broken off. It went for $750, significantly above the $100/200 estimate. Hickman’s Mexican silver pieces drew some of the highest prices of the auction. Tea and coffee articles carrying his mark went for $1250 (est. $1000/2000), while five circular trays sold for $1875, within the $1500/2500 estimate. A wall plaque of fighting cocks with a sketch by Hickman of precisely how he wanted it made went for $531.25.

The perched parrot was one of a number of animals produced as lamp bases or other items by Haeger. This 1947 version stands 15½" tall and sold for $346.50.

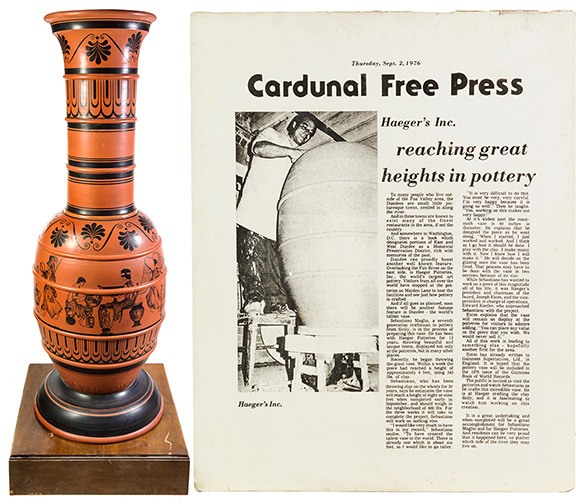

A 92½" high Classically painted vase, signed by seven individuals who worked on it, was overseen by Maglio, who, according to Estes, rose to the challenge posed by her father to create the world’s largest hand-thrown vase as part of the 1976 bicentennial celebration. “The Guinness book [of world records] was very popular then,” she said. “He hand threw the base, top, and neck, fired them together, and then hand painted it. Maglio was an incredible craftsman and a showman beyond belief.” The vase is no longer the record holder.

A 28½" high maquette of the 1976 vase with sketches sold for $1638, well over its $400/600 estimate. The vase itself, estimated at $6000/8000, was passed over during the auction but sold for $6250 afterward. A more understated Maglio piece that had a distinctive marble glaze sold for $63.

A maquette of what was to become the largest hand-thrown vase in the world in 1976 was hand thrown and hand painted and stands 28½" tall. It came with sketches of the design and construction and sold for $1638.

Made for America’s bicentennial in 1976, the Classically decorated vase is a whopping 92½" tall. It was designed and executed by Sebastiano Maglio, a seventh-generation potter who was a master at wheel-throwing. The vase was passed over during the auction but sold later for $6250.

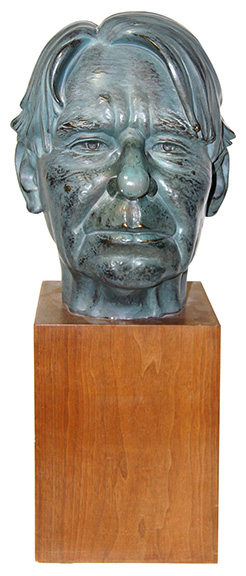

Two groupings of stalking panthers by Olsen both exceeded their estimates. One with glazed figures went for $1000 (est. $150/250), while the other grouping, which contained glazed and unglazed figures, brought $562.50, slightly above the $200/400 estimate. Olsen’s sculpted head of poet Carl Sandburg, described as a cast stone reproduction, brought $250 (est. $400/600).

Stalking panthers, some with metallic glaze and others unglazed, were a signature Haeger item after being designed by Royal Hickman and put into production in 1941. This group sold for $562.50.

Haeger designer Eric Olsen was known for his vivid red bulls, but he also produced portrait sculptures of famous people. This bust of Carl Sandburg sold for $250.

Two lamp bases by Black in bottle form with a drip glaze sold for $1071, topping the estimate of $500/700. Two unmatched ovoid-form lamp bases attributed to Black went for $630, within the $500/700 estimate.

Haeger was internationally known, having exhibited at the 1934 world’s fair in Chicago and exchanging potters-in-training with the Franz Goebel factory in Germany for many years. Two oversize Hummel figures by Goebel spoke to the admiration of one company for the other, Estes said. “Meditation” and “Merry Wanderer,” estimated at $2000/4000, went for $1500. “Merry Wanderer” was inscribed to Haeger general manager Joseph F. Estes to mark his 50th anniversary with the company, “from your friends at Goebel.”

Haeger was internationally known, having exhibited at the 1934 world’s fair in Chicago and exchanging potters-in-training with the Franz Goebel factory in Germany for many years. Two oversize Hummel figures by Goebel spoke to the admiration of one company for the other, Estes said. “Meditation” and “Merry Wanderer,” estimated at $2000/4000, went for $1500. “Merry Wanderer” was inscribed to Haeger general manager Joseph F. Estes to mark his 50th anniversary with the company, “from your friends at Goebel.”

In a first for the time, Haeger built a working factory at the 1934 world’s fair. Company ceramicists worked at one end while Pueblo Indian Maria Montoya Martinez, invited by Joseph Estes to demonstrate her traditional techniques, including firing in buffalo dung, was at the other. Once the fairgrounds were dismantled, wood from the temporary factory was used to build an addition onto the main factory, Estes said.

The museum of Haeger highlights had been plagued by a lack of storage space, forcing the rotation of pieces produced once the company transitioned to art pottery from making field tile and the bricks used to rebuild after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Many museum pieces were in the auction; some had gone to the local historical society, and any pieces left over in the showroom had been sold in special sales last spring.

“I had people hugging me and crying. It was absolutely incredible to witness and experience that emotion of people who loved our pottery,” Estes said.

For more information, see the website (www.lesliehindman.com) or call (312) 280-1212.

Sebastiano Maglio was a consummate showman who did numerous wheel-throwing demonstrations at the Haeger factory and mentored young potters.

Originally published in the May 2017 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2017 Maine Antique Digest