Part II of Berry Toy and Bank Collection Sparks Sensory Overload

March 27th, 2015

|

Bank with a black man kicking a watermelon (a.k.a. “Football Bank”), J. & E. Stevens, patented 1888, Charles Bailey’s penultimate pedestal design, cast iron, ex-Walter Tudor, F.H. Griffith, Leon Perelman, and Stanley Sax collections, Berry II’s top achiever at $270,000.

“Zig Zag Bank,” maker unknown, patented 1889 to Moses Newman and George Bennett, New York City, full- bearded wizard and jack-in-the-box connect in this stunning cast-iron, cloth, and papier-mâché bank, ex-Seamen’s Bank, Al Davidson, and Stanley Sax collections, third place among the super banks at $210,000.

“Freedman’s Bank,” Jerome B. Secor, circa 1880, cloth, wood, and painted tin, shows black man at desk who thumbs nose as hand sweeps coin into slot, no more than ten examples known, figure redressed and minor repair to head, ex-Andrew Emerine, Edwin Mosler Jr., and Stanley Sax collections, the sale’s second-highest achiever at $228,000.

Chinaman in a rowboat bank, Charles A. Bailey, painted lead, circa 1880, tray reads “Cheap Labor / Hotel / Dinner / One Cent / in Advance,” pull his queue, and he serves a rat on a platter, $96,000.

Friday’s session ended with a circa 1886 Mikado bank by Kyser & Rex Co. The coin disappears in a takeoff of the old hat trick. With a replaced coin trap, it made $90,000.

Springing cat bank, Charles A. Bailey, patented 1882, painted lead and wood, $37,200.

“125 / Motor Bank,” Kyser & Rex Co., patented 1889, possibly the rarest of the cast-iron clockwork-driven banks, when coin drops, trolley rolls forward and rings chime, repainted trap, $48,000.

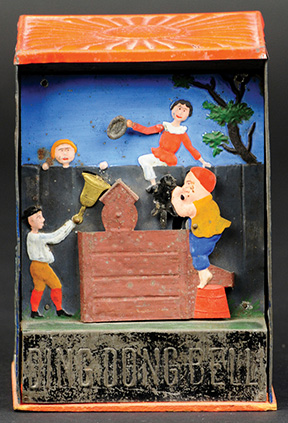

“Ding Dong Bell” bank, Weeden Manufacturing Co., circa 1888, only four known examples, boy pulls cat from well, $64,800.

Deemed the finest horse-drawn artillery toy made, this late 19th-century Pratt and Letchworth cast-iron flying artillery with mounted soldiers drawing a caisson and cannon, ex-Bill Bertoia collection, rolled merry along at $57,600.

Double-decker omnibus, unknown French maker, circa 1890, hand-painted embossed tin, sideboards post destinations, e.g., “Ville de Marseille” and “Longchamp + Joliette,” 42" long overall, matched the high estimate at $50,400.

Dentist bank, J. & E. Stevens, circa 1890, cast iron, $50,400. It is the most amusing of Charles A. Bailey’s pedestal designs; both patient and dentist fall over backward as tooth is extracted, and coin drops in the gas bag.

“Time Is Money Bank,” manufacturer unknown, circa 1880, cast iron, embossed devil-like figure with wings at top center section rotates as coin falls, ex-Edwin Mosler Jr. and Stephen Steckbeck collections, $52,800. |

Bertoia Auctions, Vineland, New Jersey

Photos courtesy Bertoia Auctions

Bertoia Auctions hit the reset button with the second round of Max Berry’s treasure-trove, offered March 27 and 28 in Vineland, New Jersey. The Berry big bling of 583 lots resoundingly topped all expectations, bringing in $2.92 million, and, as the highlight films unspooled, decisively debunked F. Scott Fitzgerald’s notion that “there are no second acts.”

Mechanical banks, 285 strong, stole the limelight. Rich Bertoia’s contention that among Berry’s mechanical bank hierarchy “the number of high-caliber pieces are so high, they just don’t show up at auction more than once in a twenty-year stretch” was clearly confirmed. Banks such as the English-made Indian chief at $22,800 (including buyer’s premium) and the “Time Is Money Bank” by an unknown maker at $52,800—both pictured here—are relative strangers to the auction scene.

The air in the gallery was so heavy, you could “iron a shirt” with it, to quote Raymond Chandler. During those angst-filled threshold moments, the free-for-all over the three rarefied mechanical banks that topped $200,000 each rivaled high-stakes poker. In Berry part I, two additional banks reached that magic milestone: the black fisherman by Charles A. Bailey at $216,000 and the preacher in the pulpit by J. & E. Stevens Co. at $252,000. The combined total for the five banks was $1,176,000.

Three out of the hallowed five were ethnic by nature, and two Berry II stellar banks, the Chinaman in a rowboat by Charles A. Bailey at $96,000 and the Mikado by Kyser & Rex at $90,000, also had racial overtones. Three of the Berry II achievers had sold at Bertoia’s 1998 auction of the Stanley P. Sax collection. Back then, Sax’s black man kicking a watermelon had brought $354,500; his “Freedman’s Bank” went at $321,500; and his “Zig Zag Bank” sold for $189,500. Twenty mechanical banks in all exceeded the $20,000 mark in Berry II, while 22 banks reached that impressive figure in Berry I.

Reigning supreme on Max Berry’s leader board was the bank with a black man kicking a watermelon, the pinnacle of Charles Bailey’s esteemed pedestal series for J. & E. Stevens. Patented in 1888 and one of only three known examples, it kicked the traces to $270,000. Rarity trumped condition here; it had a repair to the base and pedestal foot and a replaced arm. It is also known as the “Football Bank,” and its action calls for a dude in a top hat to boot a smaller watermelon into a larger one. This is somewhat baffling until we’re reminded that with mechanical banks, there’s always a twilight zone between fantasy and reality, and racial stereotypes run rampant.

The most prized, historically relevant mechanical bank was Berry II’s 1880s “Freedman’s Bank” by Jerome B. Secor (whose business was essentially sewing machines) and distributed by Ives Corp. The highly controversial Freedmen’s Bureau was established by Congress in 1865 to provide aid for and to help resettle four million ex-slaves and poor whites in the South. The bitingly satirical Berry example, one of perhaps ten known, has an intriguing paper trail. In 1939 a librarian in Mexico City found a “Freedman’s Bank” at a flea market and subsequently answered a want ad placed by Andrew Emerine of Fostoria, Ohio, seeking banks. Emerine delightedly grabbed it for $11. The black figure had no clothes, but Emerine contacted the daughter of Jerome Secor, who ably provided a new costume from a bolt of material remaindered at the Bridgeport, Connecticut, factory. It made $228,000 at Bertoia.

Arguably the most colorful and dynamic in Berry’s hit parade, the only known specimen of a “Zig Zag Bank,” fashioned of cast iron, cloth, and papier-mâché and with powerful graphics, ranked close behind Freedman’s at $210,000. A long-bearded wizard at the headboard watches a coin make a zigzag path down to the base where a papier-mâché Jack awaits and pops up out of his box as the coin hits bottom. Though a measurement was unavailable, we estimate its height to be at least 12".

The sales result of a possibly unique mechanical bank, the blacksmith lead pattern entry, indicated that rarity doesn’t always equate with desirability and exact a steep price. The unpainted pattern by an unknown manufacturer (it raises the question as to whether it ever went into production) was patented in 1905 by Frederick Plattner and shows a blacksmith poised to strike an anvil with a sledge. Ex-John Meyers collection, it raised little clamor at the hammer and sold for $6000 (est. $15,000/20,000).

Handicapping mechanical banks as to their eventual auction prices realized can prove to be as unpredictable as Lady Gaga’s wardrobe. Take, for example, Berry’s circa 1869 cast-iron “Globe Savings Fund” bank by Kyser & Rex in japanned red with gold highlights and fine casting details (est. $4000/5000). It was sticker shock in the waning moments of the sale when it spiked in value to $26,400. Conversely, a stellar J. & E. Stevens bank teller bank, with wear to one arm and a replaced coin tray, reached $43,200, well shy of its $60,000 top estimate.

Tin mechanical banks, mostly European, excelled across the board. Max Berry’s collection contained all of the known types of the celebrated hand-painted, nursery-rhyme-themed “New Line of Mechanical Savings Banks” by Weeden Manufacturing Co., Bridgeport, Connecticut. Of the two entries in Berry II, the “Plantation Darkey Savings Bank” with banjo player and dancers, patented in 1888, languished at $960, but the “Ding Dong Bell” bank,” advertised as Johnny Green, excelled at $64,800. Berry I had the rarest example of the series, a Japanese ball tosser bank with original box, which sold for $48,000. Yet to be discovered in Weeden’s 1888 series of six—collectors anxiously await sightings—are the schoolmaster, grasshopper, and Little Jack Horner banks.

Rounding out Berry’s complete set of lithographed tin Saalheimer & Strauss (Germany) Mickey Mouse mechanical banks (in Berry I a Type 2 Mickey with hands on chest sold at $33,600, and a Type 1 Mickey with folded hands brought $36,000), the March auction produced two more Mickey entries with identical action—pull one of Mickey’s ears and his tongue pops out to receive a coin. The Type 3 finger-pointing version made a handy $19,200, and the Type 4 Mickey playing an accordion sold to the tune of $20,400. That’s a rousing $109,200 for the foursome.

“Flip the Frog” by an unknown German maker, 1920s, has the comic character kicking the coin around a circular track into a trash can; at 5 1/8" high and with head repaint, it brought a restrained $6600. A bird in cage bank by George Zimmerman Co. (Germany) was another one with a Donal Markey provenance; it chirped its way to $2400. Tops among the tin banks, “The Empire Cinema Bank,” German, circa 1913, exuded star quality at $24,000. Another Bing entry, the circa 1900 tin and paper chimney sweep bank managed $4500. “The Winner Savings Bank” by Berger & Medan Mfg. Co., circa 1895, spins racehorses under its glass top—a game of chance that paid off at $20,400, nearly twice the estimate.

Not to play second fiddle to banks, the lifetime collection of bell toys was carefully gleaned by Max Berry and his wife, Heidi Berry, who were particularly drawn to that genre for its highly evocative designs and a panorama that encompasses animals, everyday people, and comic characters. Nearly 70 bell toys by N.N. Hill Brass Co., George W. Brown & Co., Kyser & Rex, Ives, Watrous Mfg. Co., and J. & E. Stevens passed tantalizingly in review.

A crowd favorite was the Captain and the Katzenjammer Kids bell toy by Kyser & Rex with their guardian, the Captain, sprawled out and pranksters Hans and Fritz on his back. By the way, Katzenjammer is German for a hangover or headache. It brought $12,000.

One of the numerous bell toys depicting patriotic motifs, and suffragettes in particular, was the 1880 patriotic bell toy by Althof, Bergmann & Co. in tin and stamped brass; depicting a marcher and mounted horsemen, it rated a salute at $15,600. Worthy of a second look and a few grins was the 1890s Jonah and the whale bell toy by Gong Bell Mfg. Co., in which Jonah tempts the whale with a dangling bell; ex-L.C. Hegarty collection and 5½" long, it was a lot of toy in sculptural detail for $2400.

Ever hear of a farthing bike? Actually, that’s a trick question or misnomer. It applies to a bicyclist penny toy by Johann Philipp Meier (Germany), a farthing in Great Britain being worth one-quarter of a penny. The 2¾" flywheel-activated toy fast-pedaled to $3900, and nearly 70 more of the increasingly costly penny toys followed.

A man chasing a woman penny toy, also by Meier, 4" long, depicts a hammer-bearing gent pursuing a frightened woman and bears a mildly bawdy caption, “My Word! If I catch you bending”; it gave a lot of action for $2700. Also memorable, a 4" long rabbits sawing an Easter egg penny toy by Georg Fischer (Germany) made $780, and a 4" long Fischer storks guarding a nest brought $1440. Also intriguing, a “Rowntree York” Punch and Judy candy box penny toy by an unknown British maker, only a tiny 2¾" high, sweetened the ante at $1320.

The dark horse, so to speak, among Max Berry’s prodigious stable of cast-iron animal-drawn rigs was an 1890s Welker & Crosby barouche (four-wheel carriage with collapsible top) that outpaced the classic Hubley Mfg. Co. three-seat brake ($5100), the Hubley four-seat brake ($6600), and the Francis W. Carpenter tallyho coach ($6000)—the latter, admittedly, with condition problems. The 17½" long barouche, drawn by two prancing blue-blanketed black steeds, in impeccable condition and the only known example, ex-Paul Dunigan collection, briskly trotted off to $24,000. (The Hubley four-seat brake in Berry II was a more common version of the one in Berry I, a custom-ordered factory-painted example that excelled at $19,200.)

From Hubley’s ever desirable advertising series, a 14" long painted cast-iron “Penn Yan” speedboat with five passengers, 1938, ex-Don Kaufman collection, made waves at $10,800. Hubley’s 8 5/8" long “Old Dutch” cleanser girl chasing dirt pull toy with stick, circa 1932, ex-Jack Brubaker and Dick Ford collections, got down and gritty at $4200.

Finally, there were what we like to call the stand-alones, which represent a variety of offshoots or subsets, yet they

deservedly galvanized the gallery to bidding excesses. A charming and very early hand-propelled, hand-painted wood velocipede coach with horse head and bridle by “A. Christian, Manufacturer, New York City, patented April 2nd 1860,” ex-Edmund and Linda Weinberg collection and Allan Katz, 32" high x 34" long, is an example of folk art at its finest. It scooted to $31,200 (est. $18,000/22,000).

The formidable 33½" long cast-iron flying artillery toy by Pratt & Letchworth, circa 1890, a painted horse-drawn cannon and caisson with six cavalry figures and four horses, ex-Bill Bertoia collection, was cited by Rich Bertoia as being in “jaw-dropping condition.” Estimated at $30,000/40,000, it passed muster and went rolling along to $57,600.

The formidable 33½" long cast-iron flying artillery toy by Pratt & Letchworth, circa 1890, a painted horse-drawn cannon and caisson with six cavalry figures and four horses, ex-Bill Bertoia collection, was cited by Rich Bertoia as being in “jaw-dropping condition.” Estimated at $30,000/40,000, it passed muster and went rolling along to $57,600.

A horse-drawn double-decker omnibus by an unknown French maker revealed stunning attention to fretwork and had appealing embossing and a fully railed stairway. The 42" long tram rated ooh la las, and the bidding stopped at $50,400, just over estimate.

From Donal Markey’s heralded collection came the exquisite 7½" high cast-iron woman at a sewing machine, a Max Sandt design, circa 1883. Exceptionally cast and giving realistic head and hand animation when the back lever is turned, it treadled to $24,000. (A Sandt clown seamstress is also known.)

The meter is still running on the Max Berry express, having surpassed $6 million. The balance of his collection will be interspersed among the offerings of a multi-consignor auction this fall. For further details on this and future auctions, contact Bertoia Auctions at (856) 692-1881 or visit the website (www.bertoiaauctions.com).

Originally published in the July 2015 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2015 Maine Antique Digest