Photography Steals the Show at Books & Manuscripts Sale

November 17th, 2013

|

This image of Mao, woven cotton brocade, was created in Hangzhou, China circa 1969. It measures 78¼" x 50¾" and sold for $510. Schinto photo.

Bidding on Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War, conceived and executed by Alexander Gardner, opened from the desk at the lot’s mid-estimate at $160,000. A silence followed. That turned out to be the beginning and the end of the bidding. The buyer, a private collector, paid $192,000. The two-volume set contains 100 original albumen photographs mounted on heavy sheets, each printed with a frame, photo credit, title, and date. Nearly half of the photographs are credited to Timothy O’Sullivan, with 16 credited to Gardner, and ten to his brother James. The others are by Barnard & Gibson (i.e., George N. Barnard and James F. Gibson), Wood & Gibson (i.e., John Wood), John Reekie, David Knox, D.B. Woodbury, W. Morris Smith, and William Pywell. All 100 images can be viewed on the Web site of George Eastman House (www.geh.org/ar/sketch The census compiled by Anne E. Peterson lists 73 known copies of the Sketch Book. Only four, including the one that sold here, are in private hands. All the others are in institutions. Besides the George Eastman House, these include the Library of Congress, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, Harvard, Princeton, and Yale, the British Library, National Gallery of Canada, and the National Diet Library in Tokyo. The Huntington Library in San Marino, California, has General Ulysses S. Grant’s copy of Volume II. It is paired with a 1967 purchase of Volume I. Copies also belong to public libraries in Haverhill, Massachusetts, (that one was acquired in 1877, “provenance unknown,” according to Peterson) and San Antonio, Texas, (theirs, her census says, was a 1940 gift).

A lot of 84 albumen photographs of the American West by A.J. Russell—plus 11 other various mid-19th-century photos—sold for $174,000. They were mounted on mat board. Most measure 9¼" x 12". One was marred by red mold. Otherwise, the condition could be characterized as “not bad” said Devon Gray. Yale University’s Beinecke Library shows about 200 Russell images, including many of these, on its Web site (http://beinecke.library.yale.edu/collections/highlights/construction-union-pacific-railroad). Three lots of photographs by William Henry Jackson (one shown) brought $10,800, $4800, and $3600, respectively. The latter two prices were below estimate. Poor condition held back these circa 1880 mammoth format (approximately 16¾" x 21") albumen photographs of the American West and Mexico. |

Skinner, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts

Photos courtesy Skinner

At the sale of fine books and manuscripts at Skinner’s Boston gallery on November 17, 2013, a 1799 letter signed by George Washington’s private secretary Tobias Lear announcing Washington’s death to President John Adams made $108,000 (including buyer’s premium). An enigmatic ten-word note (“I omitted the snow on the roof, distrusting the premonition”), penciled by Emily Dickinson, brought $28,800. A medieval Latin text manuscript by Peregrinus of Opole in its original 1376 binding fetched $42,000. They are treasures all, but 19th-century photography of the Civil War and American West provided the main excitement of the auction.

The top lot at $192,000 was a first edition of Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War. Arguably our nation’s most important photographically illustrated book on any subject, the two-volume set of 100 albumen photographs—a project conceived and produced by Alexander Gardner (1821-1882)—is also the Civil War’s most famous pictorial record. Published in Washington, D.C., by Philp & Solomons directly after the war’s end, it sold to an absentee bidder, whom department director Devon Gray identified as “a collector.”

The images, 50 in each volume, are arranged chronologically from Manassas to the dedication of the monument at Bull Run. Harvest of Death, Gettysburg by Timothy O’Sullivan is one of the book’s most recognized images, showing bloated war dead lying in a field where otherwise food would be growing. It was disseminated separately, and widely, during Reconstruction. For its catalog cover, Skinner used another of the book’s enduring icons, Gardner’s President Lincoln on Battle-Field of Antietam, which shows, against a backdrop of white-canvas camp tents, a dozen uniformed soldiers, General George McClelland, and Lincoln in his stovepipe hat towering over them. There is also John Reekie’s A Burial Party, Cold Harbor, Va., featuring a lineup of skulls, limbs, and a disembodied boot on a wagon, ready for carting away by one of the African Americans assigned to gather and bury these sadly neglected remains.

The fact that this copy of Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War landed at Skinner swelled the hearts of the local photography-collecting community with pride, even if they couldn’t even dream of walking away with it. One might expect that this kind of rarity would have found its way to a New York City auction house. A copy had sold at Christie’s on May 18, 2012, for $122,500. Previously, I wrote about a copy that was sold for $156,000 on April 9, 2008, at Bloomsbury Auctions, before it merged with Dreweatts and closed operations in the United States. (“A Civil War Collection Is Sold on Anniversary of Lee’s Surrender,” M.A.D., July 2008, pp. 1-3-C.) But Skinner was more than up to the challenge, offering this copy on the weekend of the 37th annual Boston International Antiquarian Book Fair. Only one other has gone higher, according to the auction records I could find. A second edition, it fetched $194,500 at a rare books auction at Heritage Auctions in New York on April 11, 2012, and the price included five loose duplicate photos.

So how did this copy come to Skinner? It was consigned by someone Gray described as “a private person” living in New England who didn’t know its value. “They had something else for us and said, ‘Oh, we have this book too.’ So I called them and went over.” What she found besides the Sketch Book were “lots” of other books not necessarily salable at auction. “And that can be a problem. You can have a book worth absolutely nothing right next to one worth $500, right next to one worth $20,000. It’s hard [for an untrained person] to tell.” A former book dealer, Gray went through everything, separating them into piles. “I said, ‘yard sale,’ ‘eBay,’ which means a lot when people are downsizing or needing to leave a property. So I think that’s part of why it worked. I was able to get in my car and help.”

Each volume of Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War is a 12¾" x 17" oblong—an unwieldy— shape. “It’s the kind of book that’s physically hard to handle. It’s awkward, and it’s heavy,” said Gray. “So it’s very easy to flip it open and then see the cover fall off.” Fortunately, this copy’s covers were attached, and there had never been any repairs to the binding. There was a little water staining, and one of the tissue guards was torn. “But that’s it. In terms of condition, I’d give it a B plus for the binding and an A minus for the contents,” Gray said.

The exact number of copies of this book is unknown. After Gardner’s death, Albert Ordway advertised a few copies and miscellaneous plates for sale in the Army and Navy Journal for July 12, 1884, claiming that only 200 sets were made and the negatives destroyed. This number, repeatedly cited, has not been confirmed. Anne E. Peterson, curator of photography at the DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University (SMU), in Dallas, Texas, has posited that far fewer copies of this opus were published. The author of a Sketch Book census, which lists the locations of 73 copies, Peterson has made her assertion for several reasons. First, judging from all the different bindings she has seen, she believes the book was produced only as orders for it came in. Second, it was undoubtedly a hard sell. A costly item, the set was originally offered by subscription for $150, which is equivalent to approximately $2300 today. It is a sum not many would have been likely to spend, she believes, since most wanted to forget about the war once it was finally over.

Peterson also pointed out that the creation of each book required time-consuming hand labor. Each 7" x 8 15/16" image in the book was individually printed and mounted at a time when no technology could reproduce the pictures photomechanically. She wonders how much time Gardner and his assistants could have devoted to this task. Even the known number of copies required the printing of 7300 images, and staying up all night to work was not an option. “They needed sunlight to make the prints. That means working only on sunny days,” Peterson said.

About the timing of publication she also has an opinion that differs from what has been assumed for decades. In most descriptions, it’s given as 1865-66. (Neither edition is dated, although the first states “Incidents of War” as part of each photo’s caption, while the second omits that phrase and adds plate numbers.) But she doubts any copies could have been readied as early as 1865, given that the war had ended that spring. Besides the daunting task of making the prints, Gardner first had to select the 100 images from the nearly 3000 glass negatives he and his fellow photographers had made. Then he had to write the text.

Each image has a long caption (some are several paragraphs), and the writing is compelling. For one thing, he certainly knew how to choose the telling detail. For example, the caption for A Burial Party reads in part: “Among the unburied on the Bull Run field, a singular discovery was made, which might have led to the identification of the remains of a soldier. An orderly, turning over a skull upon the ground, heard something within it rattle, and searching for the supposed bullet, found a glass eye.”

Many people wonder how a photographer could have written such accomplished prose, but Peterson is among those who aren’t surprised by his skill. Gardner’s background was in newspaper work. In his native Scotland he had owned and edited the Glasglow Sentinel. “It’s more unexplained how he got into photography than writing,” she said.

Gardner’s amateur study of chemistry and optics may have led him naturally to photography. At any rate, he was adept enough, when he emigrated from Scotland in 1856, to become Mathew Brady’s key assistant in New York, then to become manager of Brady’s studio in Washington, D.C. A widely circulated story has it that Gardner went out on his own in 1862 because he was angry at Brady for not crediting photos properly, leaving the public with the impression that they were made by Brady himself, rather than just marketed by him. Peterson believes, instead, that Brady was having his usual financial troubles and unable to pay Gardner, who probably decided he would be better off starting a business of his own. After all, a studio’s name, rather than that of an individual photographer, often appeared on 19th-century portraits, just the same as, say, Bachrach’s name appeared on portraits in the 20th century.

Peterson has written an article that goes into more detail about the life and work of this pioneering photojournalist. (“Alexander Gardner in Review,” History of Photography, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 356-67.) She is planning to write more and believes he deserves a full-fledged biography. He made the first photographs of American war dead on a battlefield—at Antietam. He photographed Lincoln more than anyone else. He also published a portfolio of photographs of the American West, Across the Continent on the Kansas Pacific Railroad. One of only four copies known is at SMU. The other copies are at the Boston Public Library, the Mercantile Library in Cincinnati, Ohio, and the Missouri Historical Society. “It would be a real coup for an auction house to land another copy of that,” she said.

One lot of 84 albumen photographs of the 19th-century American West by Andrew J. Russell (1829-1902) did well. The loose 9¼" x 12" images, mounted on mat boards, show mountains, valleys, canyons, rock formations, and other vistas along with key scenes from the building of the transcontinental railroad. The latter included images of bridges, tunnels, machine shops, station houses, track, and engines, and group portraits of important railroad history personages, e.g., Leland Stanford. Perhaps most notably, there were at least four images of the celebratory driving of the last spike, also called the Golden Spike, on May 10, 1869, when the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads joined at Promontory Summit, Utah. Russell published a book circa 1869, The Great West Illustrated in a Series of Photographic Views, that contains 50 images. By Gray’s count, this lot had 43 of those 50.

The consignment came from a house that Skinner’s European and Continental department had been sent to assess. That explains the estimate ($3000/5000), characterized as “ridiculous” by one observer. “Golden Spike” scenes alone have been sold for $20,000 to $40,000. (For example, at a Swann Galleries sale on March 23, 2010, an example brought $43,200.) Nonetheless, bidding began from the desk at $3250. Multiple competitors in the room, on the phone, and on the Internet pushed and pulled at a steady pace. A man who had driven a red Tesla to the sale dropped out at approximately half the value of his $70,000 car. Another man in the room came in at that point. A third waited to $100,000 or so before coolly asserting himself. At $174,000 the photos were his. A member of the trade? He was, and although he gave his business card to an underbidder, he did not want to give his name to M.A.D.

After the sale, I phoned Susan E. Williams, former curator of the Oakland Museum of California’s Andrew J. Russell Photography Collection—i.e., the glass negatives from which these photos were printed. Now retired, she continues to study Russell as an independent scholar. Besides his work in the American West, Russell photographed the Civil War, said Williams, who has written about that part of his career. (“Richmond Again Taken: Reappraising the Brady Legend through Photographs by A. J. Russell,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 110, No. 4, pp. 437-60). That’s how he became a photographer, she told me.

Briefly recounting the life of this New Hampshire native, who is well known in photography circles but not otherwise, she said he apprenticed in his first career (painting) in Nunda, New York. Afterward, he took a studio in Hornellsville. When the Civil War began, he used his talents to paint a large panorama to inspire enlistment. In 1862, he raised a company of soldiers and went to war as a captain, joining the 141st Regiment of the New York Infantry. He was stationed in Washington, D.C., assigned to its defense. In 1863, he was transferred to Alexandria, Virginia, and began to work with the U.S. Military Railroad. “And because they wanted photographs of the infrastructure and all their new, beautiful engines, he was given that assignment,” Williams said. First, though, he had to learn how to photograph. Williams said he hired a man to teach him. He apprenticed for three months. “After that, he was able to photograph for the rest of the war.”

Since this auction included the work of two Civil War photographers who went on to photograph the American West, readers may have the mistaken impression that this was a common progression. Among major figures in the field, “Only Russell, Gardner, and Timothy O’Sullivan went west after the war,” Williams said. She also wants people to know that Russell’s middle name was not Joseph, which is how his middle initial “J.” is often interpreted. “He never wrote other than ‘Andrew J.’ or ‘A.J.’ There is no evidence to say his middle name is ‘Joseph,’ although that was his father’s name.”

Williams left a message with Skinner for the buyer of the Russell book, hoping he’ll be in touch with her. She believes he got “a bargain.” As she figured it, “He got the eighty-four [American West images] for a little over $2000 each, which is cheap.” Williams estimates that only about 50 copies of Russell’s The Great West Illustrated were produced. “Right now they’re scattered around archives. There are fifteen to twenty that I know of, in institutions. Who knows how many there are in private collections?” None has been sold recently, she said. The lot sold at Skinner is the closest approximation. “It’s a very important collection to keep together,” she said.

Three lots of work by a third photographer, William Henry Jackson (1843-1942), could have been another highlight of this sale, if not for their very poor condition. As they were (foxed, faded, chipped, and torn) they went to the buyer of the Russell book for $10,800, $4800, and $3600, respectively. Mammoth format (16¾" x 21") albumen photographs of the American West and Mexico, the landscapes were made by Jackson in the 1880’s. Better known for his work as the official photographer for Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden’s United States Geological Survey of the Territories, Jackson made these images while working on commissions from various railroad companies.

If only they had been cared for. Who let them get this way? “They may have come from an institution,” said Gray. She wasn’t sure because they arrived at Skinner before she got there in February 2012.

The sale’s total was $1,140,198, with an 85% sell-through rate on the 497 lots offered. The department’s next sale is scheduled for May 31. What’s in store? “I’m sitting here in an empty room. I have to make it rain again,” Gray said.

For more information, contact Skinner at (617) 350-5400 or see the Web site (www.skinnerinc.com).

Originally published in the February 2014 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2014 Maine Antique Digest

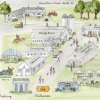

A lot of 91 stereoviews brought $4800 (est. $1000/1500). The bulk of them were 51 by Carleton E. Watkins and 23 of Wesleyan Grove Campground on Martha’s Vineyard (examples shown). These alone would not account for the very strong price, however. Devon Gray said that the very competitive bidding was inspired by four images of the Union Pacific Railroad, possibly by A.J. Russell.

A lot of 91 stereoviews brought $4800 (est. $1000/1500). The bulk of them were 51 by Carleton E. Watkins and 23 of Wesleyan Grove Campground on Martha’s Vineyard (examples shown). These alone would not account for the very strong price, however. Devon Gray said that the very competitive bidding was inspired by four images of the Union Pacific Railroad, possibly by A.J. Russell.