The 2014 Philadelphia Antiques Show

April 25th, 2014

|

The carpeted, spacious convention center space was turned into an elegant antiques show but not an intimate one. Shoppers could see an entire stand and not go in to make a discovery. There were complaints about signage; it was hard to see the names of the dealers, and the booths were not numbered. A floor plan was some help. The loan exhibition was in the middle of the show space, and some dealers said they wished it were at the back. Cross aisles were a big improvement over last year’s plan.

The chandelier by Samuel Yellin for the New York Federal Reserve, 1927, was $240,000 from Bernard Goldberg.

The salesman’s sample lawn mower, nickel-plated, 1890, 30½" x 12" x 9", was $8500 from Hyland Granby Antiques, Hyannis Port, Massachusetts.

The early 19th-century Indian printed quilt from the renowned Florence Peto collection (she wrote some of the early books on quilts) has been in the collection of Don and Trish Herr of The Herrs Antiques, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, for a generation. They offered it for the first time at the Philadelphia show, and a major museum bought it. The price was $28,000. The William Will quart pewter tankard (left) was $50,000; the miniature tin coffeepot has the initials of Willoughby Shade, a Montgomery County, Pennsylvania tinsmith. It is 3½" high, and its provenance includes the Robacker collection. It was $10,000. Don Herr thinks it was made for a child.

The Boston bow-back Windsor chairs were $12,000 for the six at a Pennsylvania farm table priced at $19,500. The Pennsylvania schrank was $29,500, and the Pennsylvania tall chest, $19,500, all from Mark and Marjorie Allen of Gilford, New Hampshire.

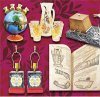

Pewter dealers Bette and Melvyn Wolf of Flint, Michigan, bought the measures, the plates, and the platters at Pook & Pook on Friday morning and offered them for sale on Friday night. The English measures were $6950; the dozen English plates, six showing, and the six platters, 1749-84, all with an English crest of Joseph Spackman, were $7950 for all of the plates and platters.

A 1790-1800 Baltimore Federal press on chest, mahogany veneer, with a pierced crest, was $39,500 from H.L. Chalfant.

The wall of chairs—all child-size—at Nathan Liverant & Son, Colchester, Connecticut, showed a great variety of small seats. Not all were for sale. Some, including a horn chair and an Adirondack-style root chair, came from Arthur Liverant’s personal collection. The child’s bow-back Windsor was $1650; the child’s Windsor highchair in old mustard paint was $18,500. A New England ladder-back chair sold, as did four others. |

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

For more than half a century, 53 years to be exact, the Philadelphia Antiques Show has been the place to find some of the best American antiques on the market. Getting a booth at the Philadelphia show was the aim of aspiring dealers. For years, a long line of collectors, advisors, and private dealers arrived for the early opening hoping to make discoveries, and they paid a premium to get first dibs. Some saved up all year to buy just one treasure at the Philadelphia show.

This year the show began its April 25-29 run with the fundraising preview party, which had a $600 admission for 5 p.m. and then lesser amounts for the party that began at 6 p.m. Fundraising was for Penn Center for Human Performance at Penn Medicine. The line for early admission was short, about 15 people. In this digital age, dealers had sent pictures of what they thought their clients might want and offered to hold it for them for the first hour or to sell it to them ahead of time. A large crowd is not necessary for a successful show on the level of the Philadelphia show. The finest works of art for sale at this show were not for the beginner or even the furnisher. This stunning show was for the collector, and although their ranks may not be growing, they are a passionate group and bought some significant furniture, paintings, maps, silver, China trade porcelain, weathervanes, folk portraits, and portrait miniatures. Some works of art were left behind. That happens at every show.

The Spitler chest that had sold at Freeman’s in April 30, 2012, was front and center in the booth of Philip H. Bradley Company and a show-stopper with its red, white, and blue compass-made designs of hearts, tulips, and birds. All cleaned up, it was $675,000. Patrick Bell and Edwin Hild of Olde Hope Antiques offered a pair of oil on board folk paintings of Jessie and Sally Stedman, signed and dated by Asahel Lynde Powers of Chester, Vermont, in 1833. Both abstract and realistic, they were $585,000. The weathervane on the table beneath them, a deer frozen in time with a rich yellow patina, an object of quiet elegance, was $38,500.

Kelly Kinzle sold a very large carousel lion carved by E. Joy Morris in Philadelphia. It was the lead figure in the 1902 carousel in Lakemont Park in Altoona, Pennsylvania, and had 95% of its original paint. The cherry secretary with its arched bonnet top, dentil molding, and pinwheel rosettes, a classic well-proportioned example of the Colchester, Connecticut, school of cabinetmakers, was sold by Arthur Liverant.

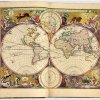

Peter Eaton sold his reverse-serpentine desk made of the finest mahogany with oversize ball-and-claw feet, big brasses, and a block and shell-carved interior. He said it was the finest of the type he has ever owned. Amy Finkel sold a pair of English sconces embroidered very early in the 18th century and of such high quality they made American needlework look provincial in comparison. James Kilvington sold a tiger maple flat-top high chest, made in the Dunlap shop in New Hampshire. Frank Levy sold a New York five-legged card table without any carving, a sculptural form, which he said he could have sold again to a collector of modern paintings. Lori Cohen of Graham Arader Galleries offered a lesson in the mapping of Pennsylvania with maps by three generations of the Scull family of surveyors. She said by the end of the show she sold half a dozen important maps, including one of the Scull maps with original color. Elle Shushan sold 17 portrait miniatures. Polly Latham sold more than 17 pieces of China trade porcelain, and Guy Kaplan sold jewelry of all kinds from all eras.

Judith Loto sold lots of books including more than 75 copies of Start with a House: Finish with a Collection by Leslie Anne Miller with Alexandra Kirtley and photographs by Gavin Ashworth; it is a plea for others to do likewise. A collector, whose husband, Richard Worley, is chair of the advisory committee for the antiques show, Miller hopes that by writing about what fun it has been to collect she will inspire the next generation. They will have to be well heeled to come close to this fine collection, and it will take time.

It is too soon after publication to measure the book’s impact, but some business was done at the show. As one dealer put it, “A third of us did well; a third sold nothing at all; and the rest may not have made expenses.”

The Philadelphia show was in crisis this year. Fourteen dealers elected not to return to the show because of the expense of union help and the Philadelphia business tax, which, though not huge, adds to the bill for the cost of the show. There is a great deal of paperwork and the threat of fines. The dealer list that was printed in the invitation had the names of two dealers who had not signed contracts and were not there. The 50 dealers who came were quite enough to put on a stunning display in the cavernous, carpeted space of the Pennsylvania Convention Center.

Catherine Sweeney Singer, who had been brought in as the director to revamp the show, was unfortunately hit by a taxicab while crossing Third Avenue in New York City on March 26 just as she was getting the Philadelphia show up and running. Her staff came to her rescue. She arrived on Thursday evening in her wheelchair recovering from a broken ankle and nose and cheered the dealers on. On Friday night she welcomed patrons. She hopes to be walking by summer.

The preview party was well attended. Food stations and bars in strategic locations offered good food and wine and spirits, making it a festive event even without champagne. On Saturday the gate was swelled by those coming to a Deerfield party to celebrate the loan exhibition from Historic Deerfield, and those attending the Antiques Dealers’ Association Award of Merit Dinner at 8 p.m. after the show closed, honoring much-loved Winterthur professor and author Brock Jobe.

Attendance was poor on Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday, gorgeous days for golf and gardening. “This is a two-day show stretched to five days,” said one dealer, a sentiment echoed by others. Many wondered if the show would go on now that the three-year contract with the convention center is over. The consensus was that it will. It will not be in the big space. Where it will go has not yet been announced. It may be a much smaller show and move to a smaller venue. Penn Medicine, the beneficiary, does not want it to move out of the city to avoid unions and taxes. Others think it would be a fine boutique show in the suburbs. Some creative planning is necessary.

“There is a lot of rebuilding to do,” said Singer. “The core dealers are a terrific group. My goal is to return the show to its position as a destination for all serious collectors.”

The role of the antiques show has changed. The successful shows are the design shows that offer one-off and limited-edition works for those who collect contemporary art and the masterpiece fairs that focus on art. They break down the barriers between painting, sculpture, academic and self-taught, and the decorative arts; it is either art or it’s not. At the other end of the spectrum, the grassroots shows, with more affordable antiques, are having a comeback. The Greater York Antiques Show, now under new management with Mitchell Displays, Inc., has 15 dealers on its waiting list. Forty years ago the antiques show had surpassed the charity ball as the number one fundraiser. That is no longer so.

For more information, see (www.thephiladelphiaantiquesshow.org)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loto called Jobe the “Matt Damon of the antiques world.” Noting Jobe’s book on Portsmouth furniture, she said that it is now a $900 book, but that she was able to find one at the $75 cover price at a Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities conference many years after it had been published and was out of print; a box of them had been discovered. She emphasized Jobe’s role as a teacher, his patience, and his ability to share his scholarship. Savage said he had known Brock Jobe since his days at the College of William & Mary when Jobe was on the staff of Colonial Williamsburg. He let the audience know that Brock Jobe’s Winterthur thesis was on the Boston upholsterer Samuel Grant, a contemporary of upholsterer Plunkett Fleeson in Philadelphia. That thesis was one of the first to study original upholstery, which is so important to furniture history. Jobe then went on to SPNEA and was instrumental in organizing the storage facility in Haverhill, Massachusetts, and in publishing the collection. His masterpiece is his book Portsmouth Furniture, published in 1992. In 1992 he was the deputy director at Winterthur, and for the last 14 years he has been a professor of decorative arts, succeeding Charles Montgomery, Benno Forman, and Barbara Ward in running the Winterthur Research Fellowship Program. Brouwer, a recent Winterthur grad, now working on the Albert Sack Legacy Archive at Yale University, spoke of Brock Jobe as a professor and as a special teacher and good guide to historic sites in the U.S. and England. She said he will retire this summer and hopes he will be able to come to her wedding in Wisconsin. After Jobe accepted the finial, the “Oscar” given to Reward of Merit recipients, he complained that it was a Philadelphia finial and he is a New England scholar. He thanked his colleagues and the trade and mentioned by name Ron Bourgeault, Jack O’Brien, and Gary Sullivan (with whom he worked on Harbor and Home: Furniture of Southeastern Massachusetts, 1710-1850, his most recent exhibition and book), Clark Pearce, Stephen and Carol Huber, Peter Eaton, and Sam Herrup. He thanked his wife, Barbara, and said they met at 18 years old and married at 20—they have been married for 46 years—the best decision he ever made. Their sons, Richard and Edward, were there as was Eddie’s wife, Elizabeth. He saluted his students—11 of them were in the audience—and said they would be the leaders in the antiques trade and the art market, and would find a way to engage a changing public. “They will make art and history meaningful and relevant, essential to our life, bringing joy and creativity as they study and interpret the historical record for future generations,” he said. |

Originally published in the July 2014 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2014 Maine Antique Digest

Show director Catherine Sweeney Singer and her husband, William Singer, at the show. Catherine was hit by a taxi while crossing a street in Manhattan on March 26 and came to the show in a wheelchair after weeks in the hospital. She had a broken ankle and a broken nose.

Show director Catherine Sweeney Singer and her husband, William Singer, at the show. Catherine was hit by a taxi while crossing a street in Manhattan on March 26 and came to the show in a wheelchair after weeks in the hospital. She had a broken ankle and a broken nose. Sam Herrup of Samuel Herrup Antiques, Sheffield, Massachusetts, offered a collection of redware. The large sgraffito plate is German, $7500. A Maine redware jar was $8500; a miniature redware jar sold, and the large slipware platter on bottom shelf was $6500. A large stoneware cooler (not shown) was $6500.

Sam Herrup of Samuel Herrup Antiques, Sheffield, Massachusetts, offered a collection of redware. The large sgraffito plate is German, $7500. A Maine redware jar was $8500; a miniature redware jar sold, and the large slipware platter on bottom shelf was $6500. A large stoneware cooler (not shown) was $6500. Minutes before he went into dinner to receive the ADA Award of Merit, Brock Jobe looked at the underside of a tiger maple porringer-top table at Bernard & S. Dean Levy.

Minutes before he went into dinner to receive the ADA Award of Merit, Brock Jobe looked at the underside of a tiger maple porringer-top table at Bernard & S. Dean Levy. From left: Brock Jobe, Louise Brouwer, Tom Savage, and Judy Loto. They all spoke at the ADA Award of Merit dinner honoring Jobe.

From left: Brock Jobe, Louise Brouwer, Tom Savage, and Judy Loto. They all spoke at the ADA Award of Merit dinner honoring Jobe.