"The Fireman" Leads $2.4 Million Sale

February 23rd, 2014

|

This color study for The Fireman by Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) sold for $216,000 (est. $50,000/100,000). The 14"x 11" oil on paperboard was sold along with a photograph of the sitter, Howard Lewis. The inscription on the Rockwell photograph says, “To Howard Lewis/ the fireman who came to my rescue/ sincerely/ Norman/ Rockwell.” Rockwell should have put the word fireman in quotes. Lewis was a publishing executive, who at the artist’s request posed in a period firefighter’s uniform for the portrait that became a 1944 cover for the Saturday Evening Post. Schinto photo.

If you don’t recognize this Venice scene, that’s because it is a rear view of Saint Mark’s Square. Titled Close of Day, the 22" x 36" oil on canvas was signed, inscribed, and dated (“1909”) by American artist Walter F. Lansil (1846-1925). The painting sold to a phone bidder for $10,200 (est. $2500/3500). Another Venice view by Lansil, Along the Riva, a 21½" x 29" oil on canvas (not shown), went to an Internet bidder for $4920 on the same estimate.

This 17th-century inscribed Scottish silver quaich (good word to remember for your next Scrabble game) sold to a phone bidder for $18,000 (est. $3000/5000). It is 5½" tall and weighs 4 oz.

This circa 1850 Chinese carved rhinoceros horn on a carved wood stand sold for $114,000 (est. $25,000/50,000). The horn is 23" tall; the stand, 15½". The combined weight is nearly four pounds. A similar horn is in the collection of the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Delaware. It can be viewed on its Web site (http://museumcollection.winterthur.org); search for “rhinoceros horn on stand.”

The top lot of the jewelry section of the sale, this natural pearl necklace achieved $46,125 (est. $5000/7000). Its length is 28"; its natural pearl count is 144 (out of 145); its clasp is white gold.

Sketch of a Child, 25" x 19½", oil on canvas, sold for $24,000 (est. $500/1000). It was attributed to Federico Barocci (1526/28-1612).

This pair of Chinese cloisonné cranes, 16½" tall, sold for $24,000 (est. $1500/2500). The carved rhinoceros horn came from the same family.

This 21" fan painted in ink and colored wash on gold-flecked paper with landscape decoration, seals, and an inscription sold for $18,000 (est. $1000/3000). It was cataloged as “Yao Yun-Tsai,” and its provenance was a New York City estate. The inscription’s translation, which came with the consignment, said, “On the birthday of flowers (12th day of the 2nd moon) of the year Hsin-wei, I painted this Spring scene of the south.”

This Chinese silk embroidered robe, with no other information about it in the catalog, sold for $27,675 (est. $800/1200) to an Internet bidder, who must have known exactly what it was.

This first octavo edition of John James Audubon’s The Birds of America, published by J.B. Chevalier in 1840-44, sold to a phone bidder for $54,000 (est. $25,000/35,000). The provenance was Roland Thaxter (1858-1932), a 19th-century American botanist, then by descent to Celia Thaxter Hubbard (d. 2013), a painter and gallery owner, who lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts. |

Grogan & Company, Dedham, Massachusetts

Photos courtesy Grogan

It was déjà vu at Grogan & Company’s sale on February 23 in Dedham, Massachusetts, when a color study in oil on paperboard of The Fireman by Norman Rockwell went up. Just 16 days earlier, on February 7 in Boston, Skinner sold a charcoal on paper study for the very same portrait.

The Rockwell study sketch at Skinner, which brought $104,550 (including buyer’s premium and a little over twice the high estimate), came from a private Massachusetts collection. Grogan’s example, which sold for $216,000 (again, a little over twice the high estimate) came from the family of the sitter, Howard Lewis, who worked for the New York publishing house Dodd, Mead & Company. Neither consignor knew that the other was going to auction, but Rockwell prices being what they have been lately, it’s not surprising that each was inspired to give the market a try.

According to the family members who consigned their Rockwell illustration to Grogan, the artist met Lewis while trying to find the perfect sitter for a firefighter portrait he had in mind to paint. It had been inspired by an antique gilt frame he had found in a junk shop. The frame was carved with axes, hoses, ladders, and other firefighting symbols. On Rockwell’s invitation, Lewis went to the artist’s studio where he donned a turn-of-the-century firefighter’s uniform. Rockwell took his photograph and worked from that. In thanks, Rockwell gave Lewis the oil study and the photo, and the two were sold in one lot to someone chief auctioneer and auction house president Michael B. Grogan identified only as “a collector.” He was underbid by two other collectors, one of whom had bought Rockwell’s fireman at Skinner, Grogan said.

The finished image appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post on May 27, 1944. The original painting of the portrait with frame is in a private collection. (A full account of the Skinner sale is on p. 11-B.)

An auction house is lucky these days to have one great item per sale that does really well. Grogan had quite a few more than one, on its way to achieving a total of over $2.4 million on an offering of nearly 900 lots. That total was something of a milestone. “In my memory, it achieved the highest hammer price we’ve ever had,” Grogan declared. “A hammer in excess of two million—that’s heroic for us. We always get to one million five, one million seven. That extra little oomph made us happy.”

It occurred “partly because we had good things,” he said, “but I actually think it happened more so because the prices were stronger overall. I really felt that. I felt there was more depth in the bidding.” Much of that depth came from the Internet, he observed. “I think with the Internet we’re getting closer to the end user and buyer. With almost nine hundred lots, we had something like four or five hundred purchasers—a lot of people buying just one item or two. It’s not like in the old days when someone would come with a truck, buy forty or fifty items, load up, and take it away. That’s hard to do now, because the competition comes from all corners of the world.”

Was it, perhaps, that the Internet is supplying the retail crowd that once came to Grogan’s auctions in person? “I would like to think that,” he said. “You know the saying, ‘Once an accident, twice a coincidence, three times a trend.’ Hopefully, you and I will be talking three times from now and saying, ‘Wow, things have truly picked up.’”

The sale lasted almost 12 hours, beginning at ten o’clock in the morning with jewelry and ending with Grogan’s own specialty, rugs. “Since we break it up into disciplines, it’s fine for the bidders,” he said. “It’s an unusual person who buys across all those disciplines, and if they are unusual, then they won’t mind staying.” He laughed.

There was a surprise waiting for those who arrived at the sale after the starting time, however. No catalogs. Basing the numbers on recent live turnouts, the auction house had not printed enough catalogs. Running out was a problem, but a high-class problem, as they say.

One room bidder came in a Bentley and carried a briefcase that never left his side. Another exited directly after he lost out on a set of the first octavo edition of John James Audubon’s The Birds of America. The seven volumes, published by J.B. Chevalier in 1840-44, sold to a phone bidder for $54,000 (est. $25,000/35,000). Among the faces in the audience that we recognized was Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, curator Elliot Bostwick Davis. She did not bid on the Rockwell. She and her husband attended on a Sunday outing, looking possibly to buy things for themselves, not the MFA, she said.

Two diamond rings and a natural pearl necklace were the top three bling lots, achieving a combined $104,325. While the jewelry as a whole wasn’t as powerful a group as it had been at Grogan’s last sale, in October, it virtually all sold.

Next came silver, some of which was undoubtedly headed for the smelter. Rarities that sold well above melt value surely were not. One was a rare 17th-century Scottish silver quaich. The two-handled drinking bowl, 5½" wide and weighing 4 oz., was inscribed, “This Cup the property of John Grant of Nevie & Helen Leslie his Spouse eldest Daughter of John Leslie of Kinninvie Married at Kinninvie 14 Octr. 1680.” It sold to a phone bidder for $18,000 (est. $3000/5000).

The same phone bidder bought a mid-18th-century Boston silver cann for $9600 (est. $3000/5000). It was marked “Hurd,” possibly for Jacob Hurd (1702/3-1758), and inscribed, “The Gift of Cath ne Marriott to S. Weaver 1744.” Its height was 5", its weight 10½ oz. (For more information about the Hurd family of Boston silversmiths, see Jacob Hurd and His Sons Nathaniel and Benjamin, Silversmiths, 1702-1781 by Hollis French, or Patricia Kane’s Colonial Massachusetts Silversmiths and Jewelers.)

Much of the good Georgian silver went to the Internet. A chocolate pot on a stand by Michael McDermott of Ireland sold via the Web for $4920 (est. $2000/4000). Another Irish piece, a silver cake stand, brought $7380 (est. $1500/2000) from an Internet buyer. Internet participants also bought an English silver caudle cup and cover for $5227.50; a covered tureen, made in 1811 by Robert Garrard of London, for $5842.50 (est. $2000/3000); and a covered tankard, made in 1712 by Francis Batty II of Newcastle, for $4920. A late 18th-century American porringer by S. Emery of Boston went by way of the Internet too, for $3075 (est. $2000/3000). Same for a similar Boston example, possibly by Edward Winslow, that fetched $3075 (est. $2000/3000). I could go on. If that’s not a trend, I don’t know what is.

The best Asian material always does well at Grogan. This time, the sale’s second to top lot was a circa 1850 Chinese carved rhinoceros horn on a carved wood stand. Handed down in a Boston family that had been involved in the China trade, the horn was elaborately carved with flowers, fruit, deer, and a figure. The wood was carved into a series of stepped rock ledges and the kinds of trees that make good bonsai. According to the consignors, earlier generations of the family had lived in Macao and returned to Boston in 1857 on the clipper ship The Flying Fish. This and other Asian art and artifacts came along with them. “We’ve been selling for [this consignor] for about two years,” Grogan said, “little bits here and there.” The horn was a big bit, selling for $114,000 (est. $25,000/50,000) to a bidder Grogan described as a Chinese-born man living in the United States.

The newest member of the Grogan team is Michael and Nancy Grogan’s daughter Lucy, who is in charge of both the fine art and jewelry departments. She is now auctioneering, and the hammer was in her hand for much of the paintings portion of the sale. When View of the Bosphorus by Germain Fabius Brest (French, 1823-1900) went up, she announced that she had bidders on every phone line “and then some.” Opening at $12,000, not much beyond the high estimate, the bidding slowly climbed at about the pace of a rock climber. It was worth the wait. The large (46" x 35") signed oil on canvas of the narrow Turkish strait went for $108,000 to a bidder in the United States described by Grogan & Company as “an intermediary for an overseas client.” Overseas phone bidders were from London, Paris, and Turkey. The underbidder was on the Internet.

Many mid-market paintings did very well. These included an abstract acrylic by Friedel Dzubas (1915-1994) that went for $26,400 and Portrait of a Kashmiri Man by Alexandre Iacovleff (1887-1938), which fetched $20,400. Each artist had ties to the Boston area. Bidders also liked a Thomas Sidney Cooper pastoral landscape that went to the Internet for $15,990. Other good sellers in the fine art category are pictured.

Furniture, as everyone knows, is as soft as Camembert. From a buyer’s point of view, however, the market can be seen as full of opportunities. At this sale, there were bargains galore in tables. Then again, there was some strength in certain top-quality furniture pieces of other kinds.

“Some of those prices we haven’t seen in six or seven years,” said Michael Grogan. For example, a nice circa 1815 Classical American mahogany sofa with painted and gilt dolphin arms and winged paw feet sold for $11,070 (est. $5000/10,000). A set of ten Georgian carved mahogany dining chairs from the turn of the 19th century realized $13,200 (est. $3000/5000). And an 8'4" early 20th-century American tubular-chime carved oak hall clock that struck the hours sonorously and exactly on time throughout the sale made $13,200 (est. $3000/5000).

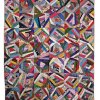

Rugs performed well, with one of the top two possibly making a new record price. Each was cataloged as having been consigned by “a Boston lady.” Both were Sultanabad carpets by Ziegler from Persia of the last quarter of the 19th century. The smaller (17'1" x 12'4") example brought $25,200 (est. $10,000/20,000). The larger (20' x 16') made $48,000 on the same estimate. Of the latter price, Grogan said, “It was remarkable because the rug had been altered in size; it had been wider. I wouldn’t be surprised if it were a record for an altered rug.” Usually they bring a third or even a quarter of what an unaltered example would bring. What made the difference in this case? “It was just so pretty, very sophisticated, perfect for a dining room, and it had no medallion,” he said.

Rugs performed well, with one of the top two possibly making a new record price. Each was cataloged as having been consigned by “a Boston lady.” Both were Sultanabad carpets by Ziegler from Persia of the last quarter of the 19th century. The smaller (17'1" x 12'4") example brought $25,200 (est. $10,000/20,000). The larger (20' x 16') made $48,000 on the same estimate. Of the latter price, Grogan said, “It was remarkable because the rug had been altered in size; it had been wider. I wouldn’t be surprised if it were a record for an altered rug.” Usually they bring a third or even a quarter of what an unaltered example would bring. What made the difference in this case? “It was just so pretty, very sophisticated, perfect for a dining room, and it had no medallion,” he said.

Of all the sale’s successes, Grogan seemed most pleased by his daughter Lucy’s turn at the podium, where she displayed an easy confidence and smooth, direct style, not unlike her proud father’s. “That’s the future,” he said.

For more information, phone (781) 461-9500 or see the Web site (www.groganco.com).

Originally published in the May 2014 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2014 Maine Antique Digest