The Winter Antiques Show 2013

January 25th, 2013

|

Peter H. Eaton and Joan R. Brownstein of Newbury, Massachusetts, sold the tall grain-painted chest (left) and the 12-panel chest under the pair of portraits by Ammi Phillips, from the artist’s “Border” period, of Ashbel Stoddard and Patricia Bolles Stoddard. The Rhode Island gate-leg table was $48,000. The compass-seat chair with parrot-beak splat and an old dry surface was made in Boston. The chest-on-chest (right), school of Moses Hazen in south central New Hampshire, has fluted quarter columns, original brasses, and an old red stain. It was $55,000. The tall-case clock (left) in a cherry case with oval inlay was made in central Massachusetts and was $26,000.

Carswell Rush Berlin of New York City offered the best Classical furniture he could muster. The reclining chair (center), the frame by Cook & Parkin and the upholstery by John Hancock of Philadelphia, was $48,000. The 1835 Boston Restauration rosewood table to the left of it was $22,500. The Boston pier table against the back wall was $84,000. The hunt board (right) is attributed to Joseph Barry of Philadelphia because the carved terms (bust portraits) are similar to those on a labeled Barry clock. It was $220,000. The Philadelphia card table (partially shown) on the back wall is one of a pair for $68,000 the pair. On that table is a Messenger & Sons sinumbra lamp, one of a pair priced at $35,000 the pair. The Duncan Phyfe chair (right) was $22,500.

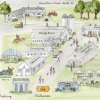

The Park Avenue Armory was all cleaned up on the outside, and the 59th Winter Antiques Show had a new design inside.

The show floor plan got a face-lift in anticipation of its 60th anniversary next year. Inside, new white fascia boards connecting the taller walls of the stands and red chairs in the aisles made the show more elegant and unified than in past years.

Lost City Arts, New York City, asked $350,000 for the Dandelion by Harry Bertoia and $1.2 million for the desk made by Wendell Castle.

Nathan Liverant & Son, Colchester, Connecticut, sold the set of Windsor chairs by Seaver and Frost and sold the pair of portraits of Amos Ransom (1761-1843), a Connecticut cabinetmaker and tavern keeper, and his wife, Jemima McCarthy Ransom (1866-1842), attributed to Joseph Seward (1753-1822) of Hampton and Hartford, together with a cherry chest of drawers attributed to Ransom. The asking price was $125,000. Liverant also sold another chest of drawers by Oliver Deeming of Wethersfield.

Jonathan Boos, New York City and Bloomfield Village, Michigan, offered five bronze Bush sculptures by Harry Bertoia. Left to right: $85,000, $55,000, $40,000, $55,000, and $100,000. Every one sold to the same client. The small paintings over them were by Max Weber ($15,000), George Tooker ($40,000), Arthur Dove ($60,000), Mark Tobey ($40,000), and Oscar Bluemner.

Peter Tillou is a dealer in Litchfield, Connecticut. He has been named the recipient of the 2013 Antiques Dealers’ Association Award of Merit, to be presented at the Philadelphia Antiques Show on Saturday, April 13.

John Wesley Jarvis’s 1821 studio in New Orleans was the inspiration for Elle Shushan’s stand to display her miniatures. The stand was designed by Ralph Harvard, who played the part of Jarvis painting his daughter during the preview. Jarvis was a New York portrait painter who wintered in New Orleans, which is Elle Shushan’s hometown, though her headquarters is now Philadelphia. Shushan said she sold every one of her star pieces and lots more and was headed to London right after the show to replenish her stock. |

New York City

The Winter Antiques Show at the Park Avenue Armory in New York City, the grande dame of antiques shows and mother of Americana Week, is approaching 60. In preparing for her jubilee next year, she got a face-lift for the January 25-February 3 show this year. Seattle-based lighting and set designer Daniel Meeker gave her white fascia boards with new signing, supported by Classical pilasters, cream-colored carpet, and a light cube with the show’s phoenix logo in the center over the bar. She looked more elegant, befitting her age.

She still takes her civic responsibility seriously, working hard to support East Side House Settlement with its focus on education and technology training for young people in the South Bronx. She is determined to be au courant and vital in her middle age. The show reflects eclectic collecting trends, all the while striving to offer the best art, furniture, silver, glass, porcelain, and jewelry from all cultures and centuries.

Even though the Winter Antiques Show is the centerpiece of Americana Week, its focus had not been on Americana for the last decades. Thirty of the 74 dealers offer American furniture, folk art, or paintings that compete aesthetically with works from antiquity, the Middle Ages, Asia, and Europe. This year two of the eight dealers showing here for the first time were dealers in old master paintings. One new dealer offered 20th-century Venetian glass, and another showed jewelry designed by post-Second World War artists. Only two—Allan Katz with folk art and advertising, and the Delaneys with clocks—offered Americana.

Americana auctions will continue to be held during the first weekend of the show, but during the following week a much larger audience arrives in Manhattan for old master paintings and drawings. It would seem logical to have more dealers who have old master paintings in the show to bring in a second wave of focused collectors and to make some new converts in the process. Alexander Acevedo, long known as a dealer in American paintings, devoted half his stand to old master paintings and sculpture, showing that they enhance each other.

“This show is all about individual objects and how their design, construction, and, of course, condition is assessed,” said Kevin Tulimieri, director of Nathan Liverant and Son, Colchester, Connecticut, specialists in American furniture. “Every morning I go to visit the eighteenth-century tapestry The Game of Nine Pins at the Keshishian stand,” he admitted.

That tapestry scene of country life, woven in Lille, France, circa 1720, makes a provocative comparison with the very best of the schoolgirl needlework, an embroidered “Fishing Lady” type work from Boston, shown by Stephen and Carol Huber. Their prices were not that far apart—around $300,000.

The show is a search for excellence but is also about the exchange of knowledge. For example, Barbara Pollack of Highland Park, Illinois, offered a schoolgirl watercolor, signed and dated (after the fact) “Hannah P. Badger 1811 & 12,” which surfaced at a small sale in New Hampshire last summer. It depicts Hannah Pearson Cogs-well and her sister Julia teaching girls at Atkinson Academy in Atkinson, New Hampshire, the oldest surviving coeducational school in America. Dealer Carol Huber walked around the show several days after it opened and noticed the tag below the charming watercolor. She realized she had in her booth a needlework of the Goddess of Liberty by that same girl, also signed and dated on the back by Hannah P. Badger, 1811 and 1812. Huber’s research shows that in 1814, Hannah P. Cogswell married William Badger, who became governor of New Hampshire. Carol Huber sold her needlework picture. Barbara Pollack said several museums took memos on her watercolor documenting women teachers and their female students in paint in 18th-century New Hampshire.

New research also brings little-known names into the marketplace. Dealers offer works not previously seen. Carswell Rush Berlin offered a reclining chair, made in Philadelphia by Cook & Parkin with upholstery by John Hancock, which will be published in the 2013 edition of Chipstone’s American Furniture journal. And he made a good case for a hunt board with carved terms (bust portraits) to be attributed to the shop of Joseph Barry in Philadelphia. Robert Schwarz had found a drawing of George Washington by Rembrandt Peale that had been scored for transfer to canvas, revealing the process by which Peale copied numerous Washington portraits. It was bought by George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

Robert Aronson of Amsterdam, the Netherlands brought a collection of 22 pieces of Delft from the most successful of all the early Delft factories, De Grieksche A (translated “The Greek A”)—more than any museum has. The factory was run by a fellow named Samuel van Eenhoorn (1655-1685), the leading provider of the finest Delft throughout Europe in the 17th century. His works, made from 1678 to 1685, are marked with a conjoined “SVE.”

Many consider the show as though it were a visit to a museum, but some come to buy. It appeared that more business was done this year than last, but there was resistance to big-ticket items. “This is globalization for the one percent,” commented one collector, saying it was too expensive but acknowledging it was a beautiful show. His wife said she has bought something at every single Winter Show; she bought some marrow scoops from Jonathan Trace and a whalebone fid from Hyland Granby, Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, to keep her record going.

It can take months for the sale of a big-ticket item. Deals are finally made. Yet some sales were made at the preview party and every day during the week. Plenty of items were priced under $5000. “I sold eleven pieces of furniture and lots of accessories,” said Enrico “Ricky” Goytizolo of Georgian Manor Antiques, Fairhaven, Massachusetts, who called to report after the show closed. “It is good to see the market on an uptick.” His prices were realistic. He said they were 40% lower than at the height of his market in the 1980’s and 1990’s. “Traditional English furniture is not out of style.”

American furniture and folk art dealers Peter Eaton and Joan Brownstein sold well. “I sold a small Queen Anne tea table, an early Connecticut tray-top tea table, a tall grain-painted chest, a twelve-panel chest, a dressing chest with attached mirror from the Seymour shop in Boston, an English or Continental spinning wheel, a tiger maple knife box, and a fire bucket,” said Peter Eaton. The theme of his booth was old dry surfaces, and his prices were in the five-figures. His wife, Joan Brownstein, sold a pair of Ammi Phillips portraits, a portrait of a child holding a spoon by Matthew Prior, a miniature of four sisters in a locket, a miniature of a boy in a red dress, and three pieces of 20th-century pottery by Edwin and Mary Scheier.

American furniture and paintings were selling on the other side of the armory. Arthur Liverant sold a pair of portraits of Connecticut cabinetmaker Amos Ransom and his wife and a chest that Ransom had made; a set of Windsor chairs by Seaver and Frost of Boston; and another cherry chest. Olde Hope sold three painted chests at the preview, and Edwin Hild said they kept on selling boxes, weathervanes, fish decoys, and decorations all week. With the exception of a yellow-painted dower chest that was decorated by the Otto family of fraktur artists, Olde Hope’s most expensive items remained unsold.

David Schorsch of Woodbury, Connecticut, sold two folk portraits, a pen wipe, a Windsor chair, and a hooked rug, but said it would be March before he knows how successful the show had been for him. Connecticut dealer Allan Katz did not have to wait until spring. His first time at the Winter Show he sold seven pieces of folk art and advertising art. Robert Young of London almost sold out his booth of English and Continental country furniture and folk art.

Some dealers in American paintings sold well. Thomas Colville of Guilford, Connecticut, had sold half a dozen paintings early in the show and sold more by the end. Jonathan Boos sold five Bush sculptures by Harry Bertoia to one client at the preview. Dealers in ancient and tribal arts were stars. Spencer Throckmorton of New York City had a record-breaking opening night by selling a serpentine Olmec mask (circa 1100 B.C.) and made seven more sales. Maison Gerard, New York City, specialists in Art Deco, sold chairs by Maison Leleu, a daybed, and an Adnet console, and had a hold on a Leleu commode with mother-of-pearl inlay and gilt bronze ornaments.

The show attendance was up, though some said many collectors were missing, some because of illness; it was a bad flu season. Some people don’t go to shows anymore because they think they can log on to dealers’ Web sites and see what they missed, but that is not possible. Most dealers do not post images of their new stock until after the show is over. Americana dealers who may take what didn’t sell in New York in January to Philadelphia in April will not post fresh stock on their Web sites until later in spring. Moreover, some dealers don’t have Web sites, and others don’t keep them current. Shows are where fresh finds are introduced by dealers, who often hold back special pieces for a year or more. That is why people line up early for show openings and why there is energy at previews.

There is so much to learn that this show brings people back again and again. Dealers reported that a lot of young people asked questions, and that designers took memos for clients’ new houses. There was talk was about prices of Upper East Side apartments being more affordable, so people are buying them and need to furnish. That bodes well for the future of the show, if it finds creative solutions for the challenge of change. Some say collectors are no longer collecting in one field in depth and instead want a variety of works of art from disparate periods and places that meet their criteria of high quality, which they hope to find in this strenuously vetted show.

The pictures and captions show a fraction what was there, focusing on Americana, M.A.D. readers’ main concern. For more information, see (www.winterantiquesshow.com).

Patrick Bell and Edwin Hild of Olde Hope Antiques, New Hope, Pennsylvania, asked $125,000 for this yellow-painted chest that had been shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974 in the exhibition The Flowering of American Folk Art and had sold at the John Gordon sale at Christie’s in January 1999. A nearly identical one is in the Barnes Foundation. Above it, the snowflake “Celebration” by John Scholl (1827-1916) of Pennsylvania was $25,500. The sheet iron and copper Angel Gabriel weathervane with traces of gold leaf was made by Mr. Whelden of Whelden & Fisher for the Wesleyan Seminary in Springfield, Vermont, circa 1846. In 1896 it had been removed from the belfry and put into storage. It was $428,000. The heart-in-hand rug (illustrated in Joel and Kate Kopp’s 1975 book American Hooked and Sewn Rugs: Folk Art Underfoot) was $24,000. Patrick Bell and Edwin Hild of Olde Hope Antiques, New Hope, Pennsylvania, asked $125,000 for this yellow-painted chest that had been shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974 in the exhibition The Flowering of American Folk Art and had sold at the John Gordon sale at Christie’s in January 1999. A nearly identical one is in the Barnes Foundation. Above it, the snowflake “Celebration” by John Scholl (1827-1916) of Pennsylvania was $25,500. The sheet iron and copper Angel Gabriel weathervane with traces of gold leaf was made by Mr. Whelden of Whelden & Fisher for the Wesleyan Seminary in Springfield, Vermont, circa 1846. In 1896 it had been removed from the belfry and put into storage. It was $428,000. The heart-in-hand rug (illustrated in Joel and Kate Kopp’s 1975 book American Hooked and Sewn Rugs: Folk Art Underfoot) was $24,000. |

Originally published in the April 2013 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2013 Maine Antique Digest